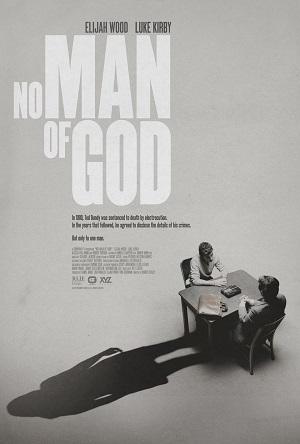

[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

In theaters, on digital and on demand August 27.

A movie needs a hero the same way a boat or car needs someone at the steering wheel. Someone has to drive the thing, and the audience has to be with them in a way that allows for some level of identification or even just cheerleading. Movies about serial killers usually get around this by sticking with the cops and their hunt of the bad guy, which makes it less about the heel and more about the white hat. No one is coming to No Man of God for the F.B.I., though, putting the new film by director Amber Sealey in a tight spot. Her film dangles Ted Bundy (Luke Kirby) as a lure, yet needs a milquetoast F.B.I. agent to steer the ship, making for an interesting, if not especially riveting or revelatory, watch.

Kicking off in 1985, Ted Bundy is over five years into his stint on Florida’s death row when the F.B.I.’s behavioral science unit meets to discuss their next round of serial killer interviews. No one seems to want to take Ted Bundy, who has a history of hostility towards the Feds, yet Special Agent Bill Hagmaier (Elijah Wood) is up for the challenge. The hope is that Bill will be able to get Ted to loosen up and talk about some of the unsolved murders that fall within his residencies and M.O., yet during their first encounter, Bill begins to understand why no one else wanted the assignment.

Ted is paranoid, hostile, deceptive, and quick to blame everyone but himself for his predicament. What’s worse, the famed serial killer is just bored enough to continue enticing Bill and others like him so that he has something, anything, to do. Bill has patience, however, and smartly deduces that he can use Ted’s boredom and vanity against him, enticing the murderer with just enough ego-boosting to develop something resembling a friendship. Bill is successful up to a point, yet he begins to realize that dancing with the devil comes with consequences: most of which are sadly unexplored.

The most telling moments of the film come not from any confession, but from the things Ted refuses to say, and the ways he dodges accountability. Throughout the film, Bill is warned by his colleagues, his boss, and even the warden of the prison that Ted is a liar and a manipulator, rendering any conversations with him to obtain actionable evidence or information futile. Anyone who can brutally rape and murder dozens of victims has a pretty clear empathy deficiency, so what possible reason could Ted have for these conversations except to play games and manipulate?

Bill is no fool, however. Alternatively playing on their tenuous “friendship,” mutual respect, and Ted’s need to self-aggrandize, Bill hopes to lull the serial killer into a sense of complacency that will allow for some small morsel of truth to tumble forth. And this is where the film is at its best, when this chess match is in full swing. Kirby’s portrayal of Ted Bundy as a skittish, frantic man who still wields his most powerful tool (verbal deception) is revelatory. Alternating between desperation, hubris, and deceit, Kirby never allows the audience to get a lock on Bundy, who writhes around on-screen with minimal movement to maximum effect.

For Ted, it’s never about him when it comes to the actual murders, but rather the clueless cops who couldn’t piece together the clues, or the idiot writers who wrote books about him yet didn’t really know him, or the cocky F.B.I. agents who think they’re smarter than him. In this way, No Man of God gets closer to the true nature of Ted Bundy than any other movie about him or serial killers in general. The kind of people who do these things don’t think or function the way most “normal” people do; a person like Bundy builds barriers in their mind that separate them from accountability, and it’s not something easily pierced.

And while Wood does good work as a decent man peeking under the hood of humanity’s scariest model, when the film ventures off into an exploration of the ways that these interviews are affecting Bill, it loses its compass. These side plots about Bill grappling with Ted’s theory that anyone could be a killer never finds any purchase in the story. Although the real Bill Hagmaier (an executive producer on this project) might have felt this way during the interviews, the film never sells it, teasing at the F.B.I. agent coming to some awful realization about his own capacity for murder when it just feels like another Bundy manipulation and deflection. Another subplot about Bill being the deciding vote to send Bundy to the electric chair comes up only to be forgotten by Kit Lesser’s script, which toys with these conflicts for Bill, yet never develops them in a way that drives the story or his growth as a character.

Sealey does a fine job behind the camera, hiding Ted early on with low, obstructed shots, as if to low-key chastise the audience for their morbid curiosity. As the film goes on, she brings the camera in closer, uncomfortably so, as if to teach viewers a lesson from the, “be careful what you wish for” textbook. Some odd year progression transitions aside, the film moves well, and never seems to suffer from a lack of locations, which keeps this story almost entirely in a prison or interrogation room.

Never exploitative, and without a whiff of sympathy or romanticism for Ted Bundy, No Man of God gets to the heart of one of America’s most infamous serial killers, albeit through a lead that needlessly gobbles up too much of the film’s oxygen. This is a film about a caged animal with a gift for deceit and obfuscation, and one man’s attempt to punch through that to grab a few crumbs of truth. At the end of the day, most of that truth revolves around Ted being a coward and a liar, and while it’s not a particularly pleasant or fun viewing experience, at least it’s an honest one. It’s not a film that Ted Bundy would have enjoyed, but it’s the one his victims deserve.

Comments on this entry are closed.