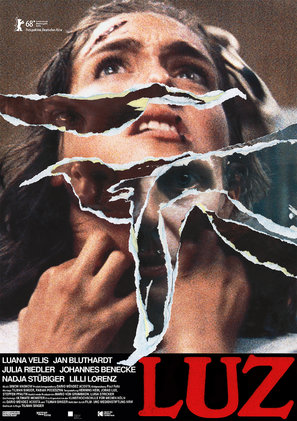

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

Usually, when I find out that a film is compared to the Canadian body-horror director David Cronenberg, then had it pointed out that it was originally director Tilman Singer‘s thesis project for a film studies class, and shot on 16mm, to boot, I’d probably run screaming from the room because of the impossible possibilities of escaping the pretension inherent in such a movie. Thanks to the unrelenting approval of film festival friends, however, I sat myself down and watched Luz, and found myself hypnotized.

“Luz begins as a young female cab driver drags herself into a run-down police station. However, a demonic entity follows her there, determined to finally be close to the woman it loves.”

Many of the reviews written thus far about Singer’s directorial debut go a long way to spoiling the film, and yet, they’re almost unnecessarily detailed. Whether or not the viewer understands precisely what’s going on while watching Luz is almost beside the point. This is a film meant to continually knock the viewer off-kilter, never quite allowing them a straightforward perspective from which to observe the action onscreen.

The most obvious and up-front example of the shifting perspective is the fact that Luz (Luana Velis) switches between speaking Spanish and German, meaning that – as the film is German – the subtitles for much of her dialogue are simultaneously subtitled in German and English. Even the other characters need someone to interpret her words, turning Luz‘s police station-set latter half into a game of telephone, as a translator takes her words from Spanish to German and quietly feeds them into earpieces.

From there, it only gets more abstract in terms of switching perspectives. As Luz tells the story of how she came to abandon her taxi to Dr. Rossini (Jan Bluthardt) and police officer Bertillon (Nadja Stübiger), she’s hypnotized so as to be back in the moment when everything occurred. There are sound effects, and she acts the events out just as if she were there, complete with smoking and adjusting her rear-view mirror.

However, as things move along, the woman with whom she was speaking – an old school friend, Nora Vanderkurt (Julia Riedler) – actually appears, and the scene switches from the police interrogation room back to the car itself, then Dr. Rossini is in the back seat of the cab instead of Nora, and flip switch flip switch flip switch flip change go the perspectives, in a heady, nearly hallucinatory 20 minutes that plays like the maddest play you’ve ever seen.

In his review of Luz for Variety, David Edelstein wrote “If Luz had been a play, I’d probably have walked out halfway through,” and I pretty much disagree. I feel like this is a film which could be converted into a play with little to no adaptation – the entire first scene, wherein Rossini encounters Nora in a bar, is a marvelous single act that could stand on its own as a short film.

The film is shot in a brilliant series of close-ups and effective wide shots, with the latter capturing that om-stage feeling and generating some remove, but it only makes the facial close-ups that much more noticeable. You’ll find yourself rewatching this to catch every nuance of expression, wondering just what a raised eyebrow might come to mean.

While just barely long enough to count as a proper feature, Tilman Singer’s Luz is a brilliant debut. It manages to be two things simultaneously. It’s most prominently the sort of film which makes you excited for the future with what it does on such a small budget and scale. However, you’ll also end up wanting to revisit all of the ’60s and ’70s grainy Satanic films which popped up in the wake of Rosemary’s Baby, doing it weirder and nastier, to see where all of this came from.

Comments on this entry are closed.