Nicolas Winding Refn created his new film Only God Forgives to make his audience uncomfortable. Director Refn knows how to plunge his cinematic knife deep into the dark recesses of the human psyche and slowly twist. To this end, Refn is not only okay if someone emerges from the theater uncertain about how they feel towards his newest film, that seems to be exactly what he is trying to achieve.

Nicolas Winding Refn created his new film Only God Forgives to make his audience uncomfortable. Director Refn knows how to plunge his cinematic knife deep into the dark recesses of the human psyche and slowly twist. To this end, Refn is not only okay if someone emerges from the theater uncertain about how they feel towards his newest film, that seems to be exactly what he is trying to achieve.

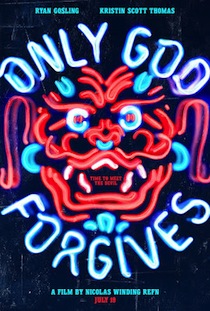

Only God Forgives is less a story and more a tone poem about Julian (Ryan Gosling), a drug runner and owner of a Muay Thai boxing club. When his brother, Billy (Tom Burke), is killed under justifiable circumstances, their mother, drug kingpin Crystal (Kristin Scott Thomas), arrives in Bangkok and demands that Julian find and kill Billy’s killer. This is complicated by the involvement of a morally ambiguous police chief (Vithaya Pansringarm).

Only God Forgives will challenge many filmgoers because each frame is beautifully crafted, but showcases gratuitous violence and does not contain a truly sympathetic character.

Except maybe Julian.

Sometimes.

Julian has a frustrating Hamlet-like inability to commit to any decisive action whether violent or sexual, the two are inextricably linked in Only God Forgives. Rumors that Julian killed his father get passed around, and there is heavy innuendo that Julian has a more than friendly relationship with his mother.

Julian has a frustrating Hamlet-like inability to commit to any decisive action whether violent or sexual, the two are inextricably linked in Only God Forgives. Rumors that Julian killed his father get passed around, and there is heavy innuendo that Julian has a more than friendly relationship with his mother.

Refn seems to compare frustrations with violence and frustrations with sex. Every character that acts out violently, meets with a severe if not deadly consequence. Most are seeking some sort of justice, but violence cannot balance the inequities. It can only destroy more.

In the same way, sex is used instead of an emotional connection. Julian’s relationship with prostitute Mai (Yayaying Rhatha Phongam) illustrates his desire for connection but his inability to open up emotionally.

The slow methodical nature of Only God Forgives, which is present in Nicolas Winding Refn’s other works, forces these images of violent or sexual acts to linger in the brain. Often a character will act out in a scene, then Refn will follow with a centered wide shot that makes us consider that character more deeply. This forced contemplation is unsettling to say the least.

The slow methodical nature of Only God Forgives, which is present in Nicolas Winding Refn’s other works, forces these images of violent or sexual acts to linger in the brain. Often a character will act out in a scene, then Refn will follow with a centered wide shot that makes us consider that character more deeply. This forced contemplation is unsettling to say the least.

Keep in mind that the violence, though troubling, is not the worst of what this film has to offer. The psychological violence dealt out from character to character is far worse. There is a dinner seen with Crystal, Julian and Mai that easily ranks as one of the more disturbing conversations ever put to film.

As with films like Gaspar Noé’s Irreversible or Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, each audience member must ask themselves the questions, “To what end was this film created?” and “Why am I participating by viewing it?”

For me, I feel that there must be room within art to explore the dark regions of the human psyche. Though disturbing, it forces us to look at how we interact with each other on a visceral level. It makes us contemplate how we view sex, violence, and how we often put them in the place of larger concepts like love and justice.

For me, I feel that there must be room within art to explore the dark regions of the human psyche. Though disturbing, it forces us to look at how we interact with each other on a visceral level. It makes us contemplate how we view sex, violence, and how we often put them in the place of larger concepts like love and justice.

I do not know that it is important that one like or dislike a film like Only God Forgives. I know that there are very few people I could recommend this film to, but I believe that it shows excellent craft and intentionality. It has forced me to ponder fruitfully topics I would normally avoid.

Be warned, Only God Forgives is for the emotionally and gastronomically stalwart. It is one of the best films I cannot, with a clear conscience, encourage others to see.

For another take on Only God Forgives read Trevan’s review or listen to the Scene Stealers podcast for more discussion.

Comments on this entry are closed.