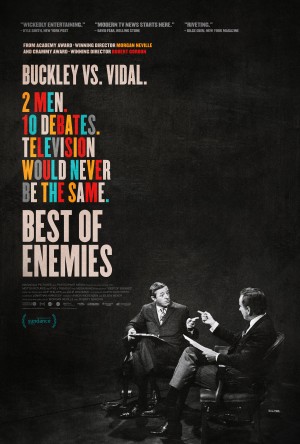

Best of Enemies, a new documentary showing soon at the Tivoli in Kansas City, attempts to show how the 1968 televised debates between intellectuals William F. Buckley, Jr. and Gore Vidal, which coincided with the presidential primaries of 1968, were a dignified exchanged of opposing ideas that devolved into the sound-bite and click-bait media culture that currently influences how Americans think about politics.

But when the viewer really pays attention to the back-and-forth barbs of the two self-important intellectuals, who speak in the kind of stiff, vaguely British-sounding patrician accents that people never seem to affect anymore, there is little more substance to their arguments than most Fox News shouting matches between liberals and conservatives.

The film tries to show that the ideas being argued over by conservative Buckley and liberal Vidal parallel the contemporary political conversation about social issues that Americans are currently struggling with: racism, poverty, the acceptance of non-straight people in mainstream society, and police brutality. Best of Enemies tries to draw facile comparisons between the late ’60s and our current increasingly tumultuous times, but the real strength of the film lies in its exploration of both pundits’ personalities.

When Best of Enemies opens with Gore Vidal giving a personal tour of his bathroom to show the various portraits of himself hanging on the wall, you should take this as a sign that the film is best viewed as an exploration of his and Buckley’s self-important personalities rather than a story that parallels our current political and media landscapes. In this way, the film, which tries to lament the currently poor state of media punditry, succumbs to the personality-driven formulas of news opinion shows by people like Bill O’Reilly and Rachel Maddow. Both men are erudite, confident in their political viewpoints, and great at hurling back-and-forth insults, but the debates themselves, many portions of which are featured in the film, often devolve into petty insults that never draw back to the larger societal issues that both men were supposed to argue over.

A scene from these debates that the film treats as a tipping point between their increasingly tense exchanges shows Vidal calling Buckley a crypto-Nazi. A visibly shaken Buckley restrains himself from lunging at Vidal, threatens to punch him, and calls him a queer. These kinds of exchanges are pushed to the foreground of the documentary, which contradicts the film’s condemnation of today’s media by focusing on the most sensationalistic moments of the debates. Near the film’s end, Buckley is portrayed as a man who was forever negatively affected, even haunted, by the debates. We are shown a televised interview that took place before a live audience near the end of Buckley’s life, in which he is shown the clip where he threatened to punch Vidal and called him a homosexual epithet. Rather than responding, Buckley sits silently, and the interview program cuts to a commercial. We are told that he then walked out of the studio and said, “I thought that that tape had been destroyed.”

Buckley is portrayed as the loser of those debates from 1968, but history has shown that his conservative, pro-business, anti-government ideals have prevailed. Buckley would be pleased to see that the Republican party has long been infiltrated by corporate interests that are actively working to diminish the role of government in peoples’ lives. And while Vidal would be pleased by the increasing acceptance of homosexuality in mainstream society, somewhat less-restrictive drug laws, and an increasingly vocal generation that speaks out against racism and police brutality, Buckley’s beliefs that all power should be held by an elite few, has prevailed. So far, history has shown that Buckley, who edited the Conservative magazine The National Review, and who was also an early supporter of Ronald Reagan, has been the most influential of the two men. Director Gordon Neville has created an engaging film whose most interesting moments lie in the personalities of both men within the clearly defined confines that are created by their conservative/liberal points of view.

However, it doesn’t entirely succeed at creating comparisons between the problems of the late ’60s and our current modern dilemmas. This is because the film’s treatment of 1960s politics are shoved to the side for the sensationalistic spats between two people who share opposite points of view, much like your average Fox News program. But Neville at least has the intelligence as a filmmaker to treat Vidal and Buckley as intellectual equals. There is no way any mainstream news/opinion program currently clogging the airwaves would give liberal and conservative pundits equal footing, in terms of their talent and intelligence. This is where Best of Enemies succeeds the most.

Comments on this entry are closed.