This last year saw a small number of documentaries that expanded the idea of what documentaries are capable of doing. Werner Herzog gave us Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which explores the origins of art and humankind with meditative grace and Herzog’s droning voice over.

This last year saw a small number of documentaries that expanded the idea of what documentaries are capable of doing. Werner Herzog gave us Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which explores the origins of art and humankind with meditative grace and Herzog’s droning voice over.

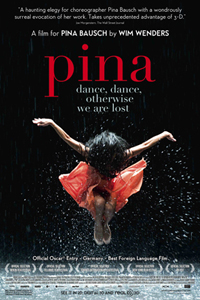

Director Wim Wenders continues down this path with his documentary, Pina, a visually impressive and emotional driven showcase of choreographer Pina Bausch’s work. Whereas Herzog would interject his own philosophical musings, Wenders allows the dance and the visuals to speak for him.

Originally Wenders intended to include Bausch in the documentary, but a cancer diagnosis and her unexpected death shifted the film from a feature about Bausch to a tribute to her work and her spirit.

Though there is no plot or cohesive storyline, this is a showcase of Bausch’s work since the mid 1970s, the film still carries us through and follows an emotional arc and various visual motifs that punctuate the dance numbers and the dancers’ remembrances of their mentor.

Though there is no plot or cohesive storyline, this is a showcase of Bausch’s work since the mid 1970s, the film still carries us through and follows an emotional arc and various visual motifs that punctuate the dance numbers and the dancers’ remembrances of their mentor.

Bausch’s work was powerful and irreverent. She often dealt with the struggle between individuals and between the sexes. Questions of freedom, sexuality, strength and individual will exert themselves througout her work.

Her pieces are at times weighty and emotional, and at other times whimsical and funny. Great care was given to the emotional pacing in Pina. We are allowed moments to take a breath or laugh in between scenes full of heartbreak and struggle.

Her pieces are at times weighty and emotional, and at other times whimsical and funny. Great care was given to the emotional pacing in Pina. We are allowed moments to take a breath or laugh in between scenes full of heartbreak and struggle.

Wenders not only allows his camera to capture the dance and the movement, but often participates in the dialogue by placing the dancers in various locations in North Rhine – Westphalia that reflect or comment on the dance that they perform.

A moment of intense personal struggle takes place in the isolated countryside to reflect the introspection within the dancer’s movements. A dance that investigates physical strength occurs in an industrial looking elevated train station. A dance about passionate love transpires on a small grassy median amongst busy urban streets. The dancers show us how in throws of our wonderful obsessive love affairs; we cannot see the bustle around us through the hazy glow of our own emotions.

Another way that Wenders translates the visual vibrancy and intimacy of the dance and dancers in Pina is through the use of 3D. It is elegantly employed and the added depth places us in the same space as the dancers.

Another way that Wenders translates the visual vibrancy and intimacy of the dance and dancers in Pina is through the use of 3D. It is elegantly employed and the added depth places us in the same space as the dancers.

At times we sit at the back of the Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, the theater that bears the choreographer’s name. Her dancers move on stage and the heads of the audience, both on screen and within the movie theater, stare transfixed. Then Wenders moves us on to the stage where the camera moves in conjunction with the dancers. The camera’s movement and the 3D allow us to participate in the dance. We are no longer passive audience members. We are part of Pina’s dance troupe.

So much emphasis is placed on the visuals and the movements of the film and the dancers that even when Wenders shoots small confessional interviews with each of the Pina’s troupe members, they never talk on screen. Instead they sit quietly, choosing whether to stare into the camera, look away, smile or cry or frown. They speak with their body movements and their disembodied voice over feels like a weird form of telepathy.

So much emphasis is placed on the visuals and the movements of the film and the dancers that even when Wenders shoots small confessional interviews with each of the Pina’s troupe members, they never talk on screen. Instead they sit quietly, choosing whether to stare into the camera, look away, smile or cry or frown. They speak with their body movements and their disembodied voice over feels like a weird form of telepathy.

Wenders has crafted a lovely tribute in Pina. Even if you’re not a fan of dance, there is plenty in this film to engage a wide range of viewers. From the rich colors and expertly composed visuals, the emotional devotion of the dancers to Pina herself, or the stunning use of 3D, there are many reasons to see this inventive documentary.

Comments on this entry are closed.