This review of All is Lost originally appeared on Lawrence.com.

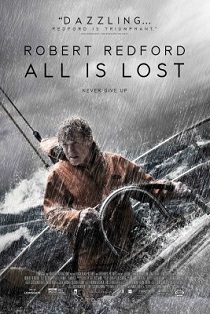

All is Lost, a stranded-at-sea survival story with almost no dialogue and a soulful lead performance from 77-year-old Robert Redford, may suffer the most from bad timing.

All is Lost, a stranded-at-sea survival story with almost no dialogue and a soulful lead performance from 77-year-old Robert Redford, may suffer the most from bad timing.

In the wake of Alfonso Cuaron’s cinematic tour de force Gravity, which puts Sandra Bullock in a similar situation — only in deep space — it’s difficult not to view All is Lost through a similar prism. The approach is similar, but All is Lost jettisons Cuaron’s thrilling first-person perspective in favor of a lower-budget, more traditional visual style and leaves most of Our Man’s backstory to the imagination.

Yes, it’s capitalized for a reason. “Our Man” is how Redford is listed in the credits, and it applies not only to his status in the movie as our hero, but Redford’s stature as an American icon. Director J.C. Chandor (Margin Call) knows this, so when Our Man finds himself on a yacht with no working communications and a hole in its side somewhere in the Indian Ocean, we immediately begin rooting for him.

View it as a metaphor or not, but the event that starts his terrifying ordeal is when an abandoned shipping container full of kids sneakers pierces the ship’s hull, sending water rushing in. It happens while Our Man is sleeping.

All is Lost also brings to mind Jeremiah Johnson, the 1972 western where Redford plays a war veteran who makes a decision to become a hermit and live off the land in virtual isolation. Our Man seems to have made a similar decision, although we are not sure how long his sabbatical was supposed to last. He obviously has money, he wears a wedding ring, and he has people that care about him somewhere.

All is Lost also brings to mind Jeremiah Johnson, the 1972 western where Redford plays a war veteran who makes a decision to become a hermit and live off the land in virtual isolation. Our Man seems to have made a similar decision, although we are not sure how long his sabbatical was supposed to last. He obviously has money, he wears a wedding ring, and he has people that care about him somewhere.

Chandor maintains two important threads throughout the picture. There’s the cause and effect: Our Man uses a combination of intelligence, intuition, and endurance to survive as he is tested by Mother Nature. Without dialogue, the film establishes the stakes for each harrowing situation and conjures up suspense. When the action slows down, it is impressive how well Chandor illustrates Our Man’s thought process moving forward.

The key ingredient to the film’s success, however, is Redford’s vulnerability. He’s trying so desperately to stay alive that he has few moments for reflection, but they register — and all without the aid of dialogue. Ultimately he must face the question of his own mortality.

Since we only have a couple of clues about Our Man’s existence before the wreck, we read what we need from two things: his actions and Redford’s face. It’s that craggy, handsome, determined, wounded, uniquely American face that gives the film its soul.

Comments on this entry are closed.