[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

This one got me, guys. Got me right in the feels.

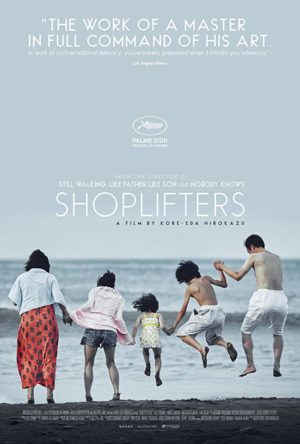

This isn’t a feel-good family movie. Shoplifters is a real good movie about family (see what I did there?). It’s quiet, beautiful, story is rich with nuance, showing ideas rather than telling.

Writer and director Hirokazu Kore-eda has done a few movies about family (Nobody Knows and Like Father, Like Son, for instance). This time, he decided to pose the question, “What makes a family?”

And then he absolutely answered it.

While returning home from a trip to the store (where they stole food and other staples while communicating with hand signals), Osamu (Lily Franky, who also starred in Like Father, Like Son) and the boy who is not his son, Shoto (Jyo Kairi), spot a very small girl outside an apartment on a very cold night. Having seen her out there before, they decide to take her home with them to feed her and warm her up, before returning her home.

Their house is a hovel where Shoto, Osamu and his wife Nobuyo (Sakura Andô) live with Granny Hatsue (Kirin Kiki, in her last movie before passing away late last year) and Aki (Mayu Matsuoka), Nobuyo’s “sister from another mister.” Though there is clearly little for the family, they share with little Yuri (Miyu Sasaki), and then Osamu and Nobuyo carry the sleeping girl home.

But upon arriving, Nobuyo realizes Yuri’s house isn’t the best place for her, and makes a quick decision to take her back with them.

The cultural differences take a minute to process. This little family looks like a blue-collar American family, not like a group of petty thieves barely getting by. The American version of this would have significantly more sex, drugs and violence – significant loss of female power and gun-fueled cash grabs out of absolute necessity or selling dangerous illegal substances to pay for legal emergency medications.

I don’t intend this to be political, but it’s a noticeable dynamic. While the family must dodge the landlord and scrape and steal, they don’t descend into a violent desperation – and perhaps it’s Japanese culture or government or a combination of both. But it is noticeable, and the lack of extremes allows the simple, and often very important, to take up space and be seen.

As the weeks pass, Yuri fits right in with the little family. She follows Shoto everywhere, and begins to learn the skills for survival, as they all have. Nobuyo works in a laundry, where she picks the pockets of unsuspecting pants. Aki is a sex worker of the peep-show variety. Osamu is a day laborer, until he breaks his foot on the job – allowing him to stay home with a small amount of workers compensation. Granny visits very distant relatives in hopes of hand-outs.

Nobody frets that the children aren’t in school (or that they’re out wandering all day). The family doesn’t scold Nobuyo for how she spends her money, or shame Aki for her line of work (although Grandma’s joshing is pretty funny). Osamu isn’t shamed or rushed into getting a new job as fast as possible. Instead they share what they have, keep each other safe, and find small ways to care for each other.

Of course, this can’t last. The police are looking for Yuri, jobs are scarce, and Shoto is growing up and beginning to question the casual morals that allow for their way of life.

The entire cast is excellent. Sakura Andô is particularly good as Nobuyo, a woman who has built a lot of walls, but never lost her humanity. She has some of the best scenes in the movie, connecting with her cast mates to create beautiful, kind moments.

Kore-eda closes the film with big questions about intentions. Was any of it real? Were these kindnesses motivated by altruism or personal need? Was it out of love or for money? And, the most important question – how much do those intentions matter, when you provide so much in emotional currency – like inclusion, intimacy, kindness, honesty, protection and tenderness?

The ending is bittersweet, but Kore-eda shows you the lessons the two children have learned from their family, like self-respect and boundaries, the difference between true love and manipulation. He also paints a beautiful picture of a family as a place where you can live as you see fit, and still be accepted, appreciated and necessary.

Comments on this entry are closed.