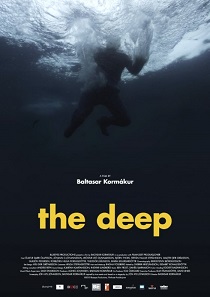

Icelandic director Baltasar Kormakur has made a very personal picture with The Deep (Djúpið), for the small island nation’s culture is rooted in the sea, and the heroes born in her wake. The true story of a group of fishermen whose vessel capsized in the frigid North Atlantic Sea in the mid-80s, the film is a character study of one man and his struggle to survive not just a terrible ordeal, but the psychological burden of having made it back when everyone else didn’t. Filmed on-location without the aid of digital effects, The Deep is a triumph both in the technical and dramatic sense, and is a wonderfully nuanced look at an Icelandic maritime disaster that is still mourned to this day.

Icelandic director Baltasar Kormakur has made a very personal picture with The Deep (Djúpið), for the small island nation’s culture is rooted in the sea, and the heroes born in her wake. The true story of a group of fishermen whose vessel capsized in the frigid North Atlantic Sea in the mid-80s, the film is a character study of one man and his struggle to survive not just a terrible ordeal, but the psychological burden of having made it back when everyone else didn’t. Filmed on-location without the aid of digital effects, The Deep is a triumph both in the technical and dramatic sense, and is a wonderfully nuanced look at an Icelandic maritime disaster that is still mourned to this day.

The picture starts in 1984, on Heimaey, one of Iceland’s Westman Islands located just off the mainland’s southwestern coast. The sailors in The Deep all chain smoke and treat their livers like used cars: the opening scene of the film going to great lengths to show how each of the characters drinks like the fishes they hunt for. Indeed, these are some salty boys, and make the guys on Deadliest Catch look like a pampered collection of shoe salesmen. Hell, even the island’s local priest seems to be on a pack-a-day habit, as if the grizzled nature of the fishing community seeped into the cleric somehow.

Yet Baltasar Kormakur is careful to give the crew of the fishing trawler ‘Breki’ enough definition to provide each of them some measure of uniqueness without slowing things down. It’s a tricky maneuver, for as an audience, we’re eager to get to the adventurous meat of the picture; yet the balance Kormakur achieves in the first act does justice to the rest of the movie, when Gulli (Ólafur Darri Ólafsson) must come to grips with everything he’s lost.

As anyone familiar with the incident (or those who have seen the movie’s trailer) knows, the Breki gets in serious trouble after the trawl (the boat’s string of fishing nets) gets caught on the sea floor. A situation that seems in-hand suddenly and tragically deteriorates, and before Gulli and his shipmates realize what is happening, the Breki has flipped and dumped its crew into the frigid 40-degree water. Without survival suits, a raft, or any other equipment, Gulli and the friends that remain face a difficult decision. Although rescue teams will likely be on their way shortly, the men can’t realistically expect to be found for hours, leaving just one option: swim.

As anyone familiar with the incident (or those who have seen the movie’s trailer) knows, the Breki gets in serious trouble after the trawl (the boat’s string of fishing nets) gets caught on the sea floor. A situation that seems in-hand suddenly and tragically deteriorates, and before Gulli and his shipmates realize what is happening, the Breki has flipped and dumped its crew into the frigid 40-degree water. Without survival suits, a raft, or any other equipment, Gulli and the friends that remain face a difficult decision. Although rescue teams will likely be on their way shortly, the men can’t realistically expect to be found for hours, leaving just one option: swim.

Fully aware that they have 20, maybe 30 minutes before hypothermia and cardiac arrest sets in, the survivors make a valiant attempt, yet only Gulli remains afloat after a short while. This is where the story’s main focus rests, for scientists are still amazed at how the real Gulli (the man’s full name was Guðlaugur Friðþórsson) survived in the water for nearly six hours. These moments, when Gulli is alone at sea, and is speaking absently to the birds circling above him, provide some of the most touching moments of The Deep. The man’s reflections on what he might have done had he been given just a bit more time, and the things he regrets, force a person to think about the confessions they might make at just such a moment, and cut deep.

Fully aware that they have 20, maybe 30 minutes before hypothermia and cardiac arrest sets in, the survivors make a valiant attempt, yet only Gulli remains afloat after a short while. This is where the story’s main focus rests, for scientists are still amazed at how the real Gulli (the man’s full name was Guðlaugur Friðþórsson) survived in the water for nearly six hours. These moments, when Gulli is alone at sea, and is speaking absently to the birds circling above him, provide some of the most touching moments of The Deep. The man’s reflections on what he might have done had he been given just a bit more time, and the things he regrets, force a person to think about the confessions they might make at just such a moment, and cut deep.

Yet Gulli makes it to land, and stumbles barefoot across something like two miles of razor-sharp lava rock before finding civilization and assistance. Spirited away to a hospital, when a doctor asks an attendant what Gulli’s temperature is upon admittance, the aid replies, “I don’t know. The thermometer doesn’t go below 93 degrees F.” Although everyone is amazed at this flabby man’s amazing feat, Gulli seems humbled by the whole event: as if he’s been given a special pass on death, if only for the time being.

As a whole, although it is primarily a character study, this is also a survival picture in that The Deep doesn’t have a physical antagonist — just the brutal, honest, and incessant presence of nature. Baltasar Kormakur directs the film in such a way as to bring that elemental force into the story as its own character, something the practical filming set-ups bear out on-screen. Kormakur spent a month shooting in the North Atlantic, with his cast and crew bobbing around in 40 F. degree water, and the grittiness certainly isn’t wasted.

As a whole, although it is primarily a character study, this is also a survival picture in that The Deep doesn’t have a physical antagonist — just the brutal, honest, and incessant presence of nature. Baltasar Kormakur directs the film in such a way as to bring that elemental force into the story as its own character, something the practical filming set-ups bear out on-screen. Kormakur spent a month shooting in the North Atlantic, with his cast and crew bobbing around in 40 F. degree water, and the grittiness certainly isn’t wasted.

The film shifts gears in the third act, when Gulli is dealt a far more challenging hand than the disaster itself: coping with the guilt of his survival. Scientists are eager to poke and prod the man so that they might unravel the riddle of his survival, which the unassuming fisherman seems entirely willing to go along with, if only so that his miracle might be of some use to somebody.

Discussions of science versus God are inevitable at this stage, for while the egg-heads insist that there must be some logical explanation for Gulli’s survival, the man’s parents are no less insistent that miracles do indeed happen from time to time. Kormakur handles these moments well, and never presumes to side with one camp or the other whilst still paying respectable credence to each point of view. It’s about the only way one could responsibly handle a conflict like this, and The Deep nails it.

There’s a haunting strings score that quietly alternates between low bass notes and the discord of screeching, high-pitched violins, which adds an eerily appropriate voice to the movie. As mentioned before, the practical effects and location shooting only further enhance the filmgoing experience, and lend gravitas and a sense of authenticity to The Deep. Having played at this year’s Seattle International Film Festival, it’s in the running for the best film going at that event this year, and is one a person wouldn’t want to miss.

Comments on this entry are closed.