Filmmakers traditionally use children in a couple of very well-established ways that are fairly well known to audiences by now. There’s the plucky sidekick (i.e. Paper Moon), the cutsie catchphrase factory (Jerry Maguire), the underdog (Little Miss Sunshine), and the feral post-disaster survivor (Aliens). It’s rare to find a child acting in one of their most common real-world functions, however: emotional ammunition. When two parents fight, and every nasty thing that could possibly be said has been uttered in several different, biting variations, the children are usually brought in to seal the deal, for it doesn’t get much more personal than involving one’s progeny.

Filmmakers traditionally use children in a couple of very well-established ways that are fairly well known to audiences by now. There’s the plucky sidekick (i.e. Paper Moon), the cutsie catchphrase factory (Jerry Maguire), the underdog (Little Miss Sunshine), and the feral post-disaster survivor (Aliens). It’s rare to find a child acting in one of their most common real-world functions, however: emotional ammunition. When two parents fight, and every nasty thing that could possibly be said has been uttered in several different, biting variations, the children are usually brought in to seal the deal, for it doesn’t get much more personal than involving one’s progeny.

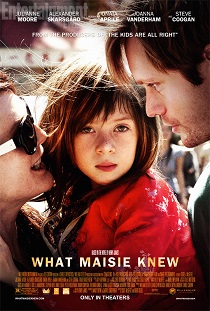

Scott McGehee and David Siegel clearly understand this, for they co-directed What Maisie Knew, a film adaptation of Henry James’ 1897 novel of the same name. The movie stars Onata Aprile as the title character, Maisie, who at six or seven years old seems perceptive and wise beyond her years. Her parents are very successful Manhattan residents knee-deep in a nasty divorce when the film starts, and neither seems particularly interested in shielding their daughter from their argumentative collateral damage.

Maisie’s father, an unrepentant narcissist (a spot-on Steve Coogan), seems to want custody if only out of habit: as if he’s used to winning every contest he enters, be it an art auction, custody battle, or simple argument. The man’s wife is little better, however, for as the mother, Julianne Moore plays a self-absorbed rock star more concerned with her fledgling career and the ongoing spousal pissing match than Maisie herself. Although both of these jackals claim to be fighting for their daughter and her best interests, each goes about it in such a way as to forego any reasonable assumption that either has even a passing interest in Maisie’s well-being. And this is very much the point, for the original novel (like the movie) has a lot to say about the responsibilities of parenthood, and the obligation every mother and father has concerning their child’s physical and emotional well-being.

As the story develops, the audience learns that Maisie’s father has eloped with his daughter’s nanny. This enrages the mom, both because she’s lost an employee, but also because the two-parent household will look much better for Coogan’s character during the custody hearing. Not to be outdone, Moore’s character quickly marries a bartender who has been a frequent hanger-on at her rock and roll parties, an act that brings the poor guy into the domestic maelstrom.

As the story develops, the audience learns that Maisie’s father has eloped with his daughter’s nanny. This enrages the mom, both because she’s lost an employee, but also because the two-parent household will look much better for Coogan’s character during the custody hearing. Not to be outdone, Moore’s character quickly marries a bartender who has been a frequent hanger-on at her rock and roll parties, an act that brings the poor guy into the domestic maelstrom.

It doesn’t take long for Maisie to start gravitating towards these surrogate parents, for her new step mother and father seem to care for the young child far more than the girl’s biological folks. This is especially true in the case of Maisie’s new stepdad, Lincoln (Alexander Skarsgård), whose own childish, innocent nature seems to allow him an easy entrance into Maisie’s heart (and he into hers). Joanna Vanderham plays Margot, the nanny/new stepmom who also discovers that despite her marriage, she’s still more of a nanny than a wife: much to Maisie’s delight. Although Vanderham does a wonderful job playing the kind-hearted, easily-manipulated nanny, Skarsgård all but steals this picture as the affectionate bartender who slowly discovers a paternal love for Maisie far more precious to him than what he feels for the girl’s mother.

The filmmakers’ decision to retain the novel’s point of view is the film’s strongest component, for by keeping the action anchored in Maisie’s experiences, through her own eyes, the picture is given a very honest voice. It’s a rare thing to find a movie about a child that is primarily meant to speak to the adults in attendance. Last year’s Beasts of the Southern Wild certainly claimed that distinction, and What Maisie Knew is no less successful. The story of a young girl coming to grips with the very difficult realities surrounding the divorce of her parents, the latter film is at its best when it’s most honest. Indeed, much like children at Maisie’s age, the truth seems to leak out of this movie in seemingly innocuous statements and gestures.

The filmmakers’ decision to retain the novel’s point of view is the film’s strongest component, for by keeping the action anchored in Maisie’s experiences, through her own eyes, the picture is given a very honest voice. It’s a rare thing to find a movie about a child that is primarily meant to speak to the adults in attendance. Last year’s Beasts of the Southern Wild certainly claimed that distinction, and What Maisie Knew is no less successful. The story of a young girl coming to grips with the very difficult realities surrounding the divorce of her parents, the latter film is at its best when it’s most honest. Indeed, much like children at Maisie’s age, the truth seems to leak out of this movie in seemingly innocuous statements and gestures.

At one point, when Margot is asking Maisie how she feels about Lincoln, the little girl responds with unconscious honesty, “I love him.” Later, when Maisie is lost and frightened, she doesn’t ask for her mother or father, but for Margot to come and rescue her. One of the interesting subtexts to What Maisie Knew is a consideration of how the events of this film will affect the young girl later on in life, and these small developments seem to hint at the beginning of just such a transformation. Yet this seems to be very much the point, for Henry James, like directors McGehee and Siegel, seem to think that this kind of thing is important: that parents should consider how their actions can alter the life of a seemingly innocent bystander watching from the wings.

And while some liberties are taken with the novel’s finer points, including the story’s original resolution, the film adaptation does a fine job updating James’ 1897 morality tale. Moved across the pond from London to New York, and set 115 years later, the cinematic adaptation retains its predecessor’s core thematic elements, and is just as relevant (if not more so) in its modern Manhattan setting. Perhaps a bit tidier in its resolution than what one would actually find in an actual custody battle of this magnitude, the film gets something of a pass in this regard because of its focus: for at the end of the day, when looking through the eyes of a child, things aren’t that complicated.

And while some liberties are taken with the novel’s finer points, including the story’s original resolution, the film adaptation does a fine job updating James’ 1897 morality tale. Moved across the pond from London to New York, and set 115 years later, the cinematic adaptation retains its predecessor’s core thematic elements, and is just as relevant (if not more so) in its modern Manhattan setting. Perhaps a bit tidier in its resolution than what one would actually find in an actual custody battle of this magnitude, the film gets something of a pass in this regard because of its focus: for at the end of the day, when looking through the eyes of a child, things aren’t that complicated.

Currently playing at this year’s Seattle International Film Festival, and in full release today, What Maisie Knew should be commended for breaking the traditional mold of children in movies. Indeed, while it isn’t always pretty, the film at least has the courage to commit to its message: the emotional and spiritual protection of children.

If nothing else, Henry James probably would approve…so there’s that.

Comments on this entry are closed.