The opening shots of documentary feature License to Operate pan over the suburbs of south central Los Angeles, one of the most notoriously violent neighborhoods in the United States. The sun-bleached, one-story homes sit in endless rows like legions of ancient Roman soldiers besieging the massive L.A. skyline in the distance. Were this neighborhood an army, it would be one long-since abandoned by its leadership, and left to fend for itself in the hot, desolate wasteland. Like a rogue army, the fragmented regiments have formed clans, segmented into strictly enforced territories, and are perpetually at war with each other: if only out of habit. An elaborate fantasy, to be sure, yet this metaphor is not entirely without a basis in reality, as the neighborhoods of Inglewood, Compton, Hawthorne, and Gardena largely fit the fictitious model above.

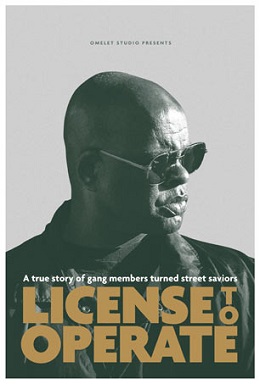

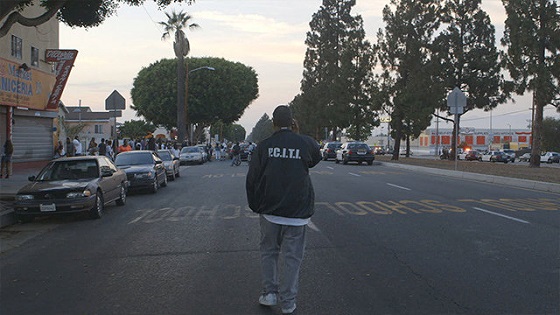

This is the focus of License to Operate, which examines the volunteer organizations that have formed in L.A. in an effort to curb violence and create lasting lines of communication between the neighborhoods and civic officials (police included). One of the leaders of this movement is Anquil Basheer, whose company P.C.I.T.I. (Professional Community Intervention Training Institute), trains community volunteers to act as intervention specialists in L.A.’s hottest neighborhoods. Many of these volunteers are reformed gang members and convicts that use their neighborhood reputation and/or street cred. to get an audience with both victims and perpetrators. Mr. Basheer and his intervention specialists routinely head out to crime scenes in the middle of the night to talk to locals, establish a narrative of events, and endeavor to curb tensions that might lead to violent retaliation.

The work that these people do represents more than just damage control, however. These men and women act as mentors and friends to teenagers and young adults in south-central L.A., and try to share some of the hard life-lessons they’ve learned with their charges. As one former gang member now working in outreach explains to the camera, the kids that he works with don’t always heed his advice or take his message to heart, but the advice is there for them to take or leave. This is something he and many others never had, and the intervention specialist thinks that it is worth it to keep trying, if only to provide one voice of reason amidst the cacophony of madness.

It seems like difficult work, for as the film shows early on, most of the teenagers and young adults are too deep into the fabric of the “bangin’” lifestyle to deviate from the community’s expectations. One young man the intervention specialists work with is named Jose, and although he seems aware that he’s on a path that’s fast-tracking him either to prison or the morgue, the thought of going against the code of the streets is unthinkable. Sure, it would be nice to be able to hang out in a gym with a member of a rival gang, but the notion is akin to treason to Jose, who dismisses the proposal outright. License to Operate is at its best when it examines this disconnect between the earnest efforts of the intervention specialists, and the realities of gang culture, as it puts the struggle into clear focus.

Sadly, the film is more concerned with telling the stories of the people involved in the intervention programs than it is with relating the history, dynamics, and successes/failures of that work on a macro level. There is a lot of time spent talking about the personal histories of the intervention specialists, and what brought them to the point where they wanted to help affect changes in the system, yet very little exploring the history of outreach programs in L.A., and what other former gang members have done in the past (or in other parts of the country). A few minutes tracking the history of the P.C.I.T.I. and other similar programs would have provided a hearty dose of much-needed context for the documentary, and might have framed the accomplishments of the featured subjects in an even more favorable light.

And speaking of results, while (again) a huge chunk of License to Operate is dedicated to examining how the featured subjects have changed, and become better people as a result of their work, there is not a lot in the way of hard statistics to demonstrate the effectiveness of this work. Director James Lipetzky saves most of his stats in this regard for the end, during a speech and via title cards just before the credits, yet it seems like something of an afterthought, and doesn’t allow the audience much time to contextualize it within the scope of all that has come before.

There’s a missed opportunity here, for if License to Operate offered statistics showing crime rates in other cities with similar population densities, and L.A.’s stats before and after the work of these intervention specialists, the film might be able to accomplish what it seems to reach for: inspiring others to take up their model. If the movie had given itself over to the data a bit more to provide some level of definition for the work that’s been done, it might well have been more inspiring than even the most uplifting reform stories presented throughout the picture. Without this, or more critical analysis of where these intervention specialists are failing, it all comes off as a bit hollow.

Indeed, Jose seems happier that he’s not in prison than enlightened by the very reasonable advice he’s given throughout the picture. Jose and other men his age are nowhere to be seen when the intervention specialists host a march through south-central L.A. near the end of the picture, which is a telling indicator of the limits of the outreach. License to Operate is currently playing at the Seattle International Film Festival, and is a heart-warming story about good people doing damn good work. If the film had dug a little deeper, and taken more time to analyze the world it lived in as opposed to the people who populate it, Mr. Lipetzky’s picture might have flirted with the profundity it nearly achieves.

Comments on this entry are closed.