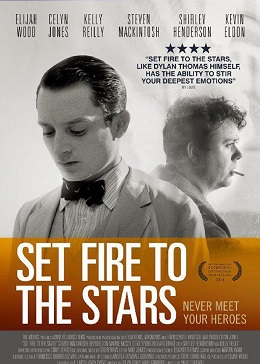

Set Fire to the Stars is director Andy Goddard’s first foray into full-length features, and is a brave, if ultimately unsuccessful, exercise in tragi-buddy-comedy. It stars Elijah Wood as real-life poet John Brinnin, who in 1950 arranged the first American reading tour for the Welsh literary legend, Dylan Thomas (Celyn Jones). The film starts with Brinnin sitting before a vaguely defined tribunal of academic types, who are grilling Wood’s character about the proposed visit. They question the somewhat flippant and visibly excited Brinnin about stories they’ve heard about Thomas’ boorish behavior, and the mayhem that is said to follow the man wherever he goes. Clever editing during the picture’s opening minutes let the audience in on the secret that Brinnin isn’t as confident about the whole endeavor as he lets on during the interview, yet he’s able to bluff his way through it, and gets the okay to bring Thomas over for an Ivy League reading engagement.

Brinnin’s admiration for Thomas’s work is established during these opening moments, and very efficiently provides the audience with just enough information about his character and motivations to set the stage for the drama to follow without bogging matters down. Brinnin is starry-eyed and giddy about the prospect of meeting his hero, and is incredulous to the rumors that Thomas is some kind of unhinged wild man. Indeed, to Brinnin, a person capable of such magnificent poetry could hardly harbor something so ugly as to fuel the reputation that follows the man.

Naturally, everything Brinnin thought he knew about his idol goes to pieces once he finally does meet the famed poet. Dylan Thomas is a hulking, loud, profane, boisterous, unpredictable tornado of a man that Brinnin quickly realizes can’t be controlled in any conventional sense. Sort of like a cross between Jim Morrison and Hunter S. Thompson, Thomas drinks too much, destroys hotel rooms, terrifies women, and generally lives to raise hell. The man is also a physical and emotional wreck, and it takes Brinnin all of about ten minutes to surmise that prolonged exposure to New York City will likely kill Thomas.

It’s for this reason that Brinnin takes the Welsh poet into the countryside, to a boathouse in rural Connecticut, where he hopes the isolation will curb the man’s more troublesome proclivities. This retreat from the public sphere upsets one of the men from the academic tribunal seen early in the picture, however. This gentleman, Jack (Steven Mackintosh), hounds Brinnin with increasingly frantic phone calls, demanding updates, and threatening vague consequences if Brinnin doesn’t keep Thomas on schedule.

It’s never entirely clear why Brinnin needs Jack or the mystery academic panel’s continued approval (although it is presumably for the trip’s continued funding). The plot of Set Fire to the Stars is sheered a bit thin in places, and this is one of them. There’s this ever-present threat that Dylan’s antics might lead to some catastrophe, yet this Sword of Damocles is never really defined. Why the audience should care about the outcome of Thomas’ visit is never really made clear, nor is the motivation or deeper personal feelings of its most interesting character. The juxtaposition between the beauty of Dylan Thomas’ poetry and the ugliness of his personality make him a fascinating subject, yet Set Fire to the Stars is content to simply revel in this instead of getting to the root of it.

An exploration of the latter consideration would have been much more gratifying, yet its absence is not what drags the film down. That dubious honor goes to the script, and the story’s seeming reluctance to amble forward at anything faster than a crawl. The set-up is promising, for it speaks to a road trip-style adventure pairing an odd-couple together for folly and laughs. This formula is hard to screw up, and has seen many different incarnations (i.e., see Get Him to the Greek, Midnight Run, Dutch, The Rundown, and Planes, Trains, and Automobiles). Yet Set Fire to the Stars side-steps this trope by planting its characters in the woods of Connecticut, where the cycle of debauchery, outrage, and introspection is simply repeated again and again.

This single-minded focus successfully conveys the central themes of the picture (keep your heroes at arm’s length, greatness does not necessarily correlate to a great person, a well-lived life demands risk, etc.), yet it leaves the movie feeling a bit hollow. Elijah Wood does an admirable job portraying Brinnin as the man’s career, aspirations, and world-views disintegrate slowly before his own eyes. It is Celyn Jones’ picture, however, and as Thomas, the man is a revelation. It’s almost worth watching Set Fire to the Stars exclusively for Jones’ performance, which delicately balances the explosive energy of Thomas with the man’s wholly vulnerable side. There’s also flashes of a canny publicist behind Jones’ eyes as Dylan Thomas, who seems to act out as much from innate, natural urges as from the conscious understanding that it is what’s expected. The man is aware of his reputation, and is nothing if not a performer: one dedicated to giving his audience a good show.

Still, all of this is drawn out through the performance, not the script, which only vaguely defines Brinnin and Thomas’ characters beyond their primary functions within the story. This is a shame, too, for there are moments in the film, like during the diner (and later, the ghost story) scene that might have allowed for some added definition in this regard. Shot in gorgeous black and white, and to good effect, the rich visual texture, outstanding performances, and intriguing material isn’t enough to elevate Set Fire to the Stars above mediocre status, where it currently rests: albeit with a whiff of promise. Currently playing at the Seattle International Film Festival, the movie would be a fun trip for any Dylan Thomas fans out there, yet is a bit lacking in content and structure for most everyone else.

Comments on this entry are closed.