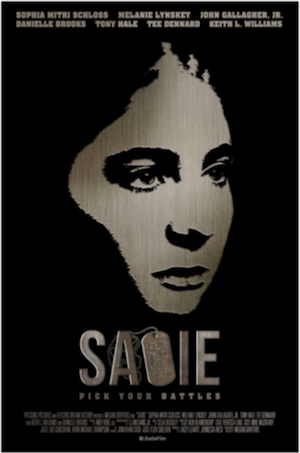

[Rating: Rock Fist Way Up]

A startling and timely update on a classic teen angst coming-of-age story, Sadie is a film about a small community whose children are a litmus test for a bigger world moving in a dark direction. A movie about a young girl coming to terms with the fact that her absentee father isn’t coming home any time soon, the film takes on more meaning in the age of ISIS, the alt-right, and Parkland, when shocking acts of violence begin to define a generation’s place in history.

Sadie opens with its eponymous character penning a letter to her deployed father, who has just volunteered for yet another rotation in the Army overseas. Sadie (Sophia Mitri Schloss) writes about how much she misses her dad, employing apologetic language that establishes her reluctance to place any blame on him for being away. Her father is a hero for serving his country, Sadie is fond of saying, so it is up to everyone else to sacrifice just as he sacrifices.

More than three years gone, this rationale isn’t enough to assuage Sadie’s mom, Rae (Melanie Lynskey), however. Rae knows her husband may return one day, but he will never come back to the family he is so deliberately avoiding. As a result, Rae has begun dipping her toes in the local dating scene’s water, resulting in the presence of a well-meaning local man, Bradley (Tony Hale), hanging around Sadie and Rae’s trailer with increasing frequency. Rae is reluctant to pull the trigger on the new relationship, though, both because of Sadie’s vocal disapproval, and because there just doesn’t seem to be any spark there.

Sparks are not in short supply when a new neighbor moves into the trailer park, though. The arrival of the ruggedly handsome Cyrus (John Gallagher Jr.) just across the lot catches everyone’s eye, Rae in particular. Sadie, struggling with her budding womanhood, bullies, and teachers concerned about the dark content of her writing assignments, now has to contend with a very real threat to her family dynamic. Smart, creative, and manipulative to a startling degree, Cyrus’ arrival spurs Sadie to take actions to assume some level of agency in a life whose reins are not at all in her grasp.

Sparks are not in short supply when a new neighbor moves into the trailer park, though. The arrival of the ruggedly handsome Cyrus (John Gallagher Jr.) just across the lot catches everyone’s eye, Rae in particular. Sadie, struggling with her budding womanhood, bullies, and teachers concerned about the dark content of her writing assignments, now has to contend with a very real threat to her family dynamic. Smart, creative, and manipulative to a startling degree, Cyrus’ arrival spurs Sadie to take actions to assume some level of agency in a life whose reins are not at all in her grasp.

With Sadie, writer/director Megan Griffiths has made a narratively-small movie that still manages to create a fully realized world stocked with authentic, lived-in characters. For example, Sadie’s best friend, Francis (the superb Keith L. Williams), is just a bit younger than Sadie, and embodies the young innocence that his emotionally crippled BFF is willfully shedding every day. A scene showcasing the pair’s first kiss, and a conversation about it afterwards, quietly encapsulates the two worlds Sadie is bouncing between. One chunk of Sadie is still a kid, to be sure, yet strong emotional currents churning inside of her threaten to capsize a childhood the young woman has prematurely outgrown.

Most of what works with these characters starts with the script, which is sharp enough to lay sufficient subterranean cable to give the audience all the information they need about these people. Sadie might not be the most emotionally stable person in the world, but she is astonishingly smart (a dangerous combination), as evidenced by her good grades and immediate understanding of subtle social cues. Francis’ world-wise grandfather, Deak (Tee Dennard), who also lives at the park, is one of the few people smart enough to keep up with Sadie. When the man speaks, his words carry layers of meaning, and provide Sadie (and the audience) with the hard truth of things wrapped up in innocuous packages. This is important, as the way these characters interact and communicate speaks volumes and eschews painful exposition moments that would have slowed the effort down.

Griffiths also makes wonderful use of color in Sadie, dressing the characters in the trailer park in muted tones that juxtapose aggressively against anything outside of that little universe (such as a supermarket). Sadie is a film about a forgotten young woman, surrounded by people who have likewise been forgotten. These people fade into the background of their communities, and Griffiths makes sure that the way they appear in her film reflects this cruel reality. Although this is just one small piece of the overall puzzle, it contextualizes of the broader thematic framework Sadie operates upon.

Griffiths also makes wonderful use of color in Sadie, dressing the characters in the trailer park in muted tones that juxtapose aggressively against anything outside of that little universe (such as a supermarket). Sadie is a film about a forgotten young woman, surrounded by people who have likewise been forgotten. These people fade into the background of their communities, and Griffiths makes sure that the way they appear in her film reflects this cruel reality. Although this is just one small piece of the overall puzzle, it contextualizes of the broader thematic framework Sadie operates upon.

At a certain point, a society has to ask what kind of effect a prolonged, nearly two-decade war has on its citizens and the kids that it brings into the world. Adolescents and teenagers coming of age in 2018 have only known a world at war: the children of these soldiers understanding a cruel, permanent reality about life that previous generations have never known. Young Sadie is very much a product of this world, fired in the furnace of aggression as embodied by a missing father whose absence only makes sense if war does. How this informs the worldview of an impressionable and emotionally confused young woman is at the heart of the story Griffiths wants to tell, which is nothing if not sobering.

Playing at this year’s Seattle International Film Festival on June 6, Sadie is a powerful film about growing up in the modern world, and how the best and worst of the next generation are dealing with that. Uncomfortable at times because of how genuine it comes across, superb writing and pitch-perfect performances elevate this movie beyond the grounded foundation upon which it rests.

Comments on this entry are closed.