[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

A based-on-a-true-story movie showcasing the inevitable corruption of absolute power, and what it means to be loyal to a people over a person, The Man Standing Next has a lot going for it despite some stumbles. Set in the headspace of one man parsing out the particulars of his duty, the film by writer/director Min-ho Woo sometimes gets lost in the psychological struggle of its lead and fails to connect the narrative to its timeline. Yet while the movie sometimes wanders in this regard, it never finds itself completely lost, and manages to stick its landing after some second act wobbling.

The film’s opening text states that it is focused on the 40 days leading up to the assassination of South Korea’s president on October 26th, 1979. The killing of a head of state is always a big deal, but coming so far into the 20th century, and in a developed country with close economic, military, and political ties to the United States, the impact of President Park’s murder hit with all the force of a runaway train.

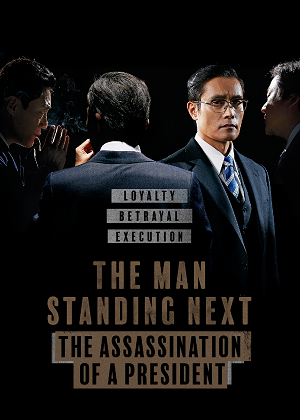

The Man Standing Next focuses on the individual behind the assassination, Kim Kyu-Pyeong (Byung-hun Lee), the head of South Korea’s C.I.A. equivalent, the KCIA. Kim is a moderate compared to the increasingly hardline, dictatorial President Park (Sung-min Lee), who has ruled South Korea with little interference for the last 18+ years. At the beginning of the film (and the 40 days leading up to the assassination) Kim comes off as wholly committed to his president and his duty as the leader of the country’s intelligence service. Yet Kim’s predecessor and friend, Park Yong-gak (Do-won Kwak), has taken all the dirty secrets of the KCIA and Park’s regime to America, where he’s planning to publish a memoir and spill all the beans, complicating things.

President Park’s insistence that Yong-gak be silenced, along with his increasingly authoritarian response to protests within the country, begin to pull at Kim’s loyalties and test the KCIA director’s sense of duty. Kim spends most of his time balancing his obligations as a loyal right-hand man to the president with pragmatic concerns about the optics of an assassination of a high-ranking exile or the public crushing of protestors. At times President Park seems to listen to Kim, yet he’s increasingly swayed by the aggressive, sycophantic advice of his chief of security, Gwak (Hee-joon Lee).

As The Man Standing Next goes deeper into the 40 days leading up to Park’s assassination, Kim finds himself stretched ever thinner between what he knows to be right versus the blind obedience expected of the KCIA’s head. Byung-hun Lee plays Kim with a quiet resolve that allows for the slightest twitch of the eye or shuffle of the feet to express volumes. And while the actor must keep most of this bottled up, it is clear that this is absolutely a choice throughout: as evidenced by the few electric moments where Lee allows the pot to boil over.

This psychological nuance and the commitment to bringing this out through Kim’s quiet 40-day struggle works well, yet weirdly, The Man Standing Next changes the names of most of the characters away from the historical counterparts. This is the first of several odd choices for the film, another being the exclusion of any personal life for the main characters, who exist only as pawns in this one narrow narrative. Sure, the film’s events are filtered through Kim’s perspective, yet taking a true story and applying reasonable conjecture as a means to unfold a plot doesn’t seem like grounds enough to change everyone’s names, just as the absence of any home life or non-professional context doesn’t seem necessary to maintain the story’s focus.

Who Kim, Park, Gwak, or any of the other characters are outside of the script’s political functionality would have gone a long way towards filling in the gaps that the sometimes-confused politicking creates. Some great work is done to connect Kim to the ideals of the political revolution that thrust him and Park into power, hinting at a backstory between the two that comes in fragments throughout, yet this kind of context is sparse. Creating characters instead of narrative components would have helped connect the audience to Kim and the other characters, who just serve as a functionality to the overall assassination plot and little more.

Visually, Min-ho Woo does fine work framing his shots to reflect the inner turmoil of Kim and the other characters, presenting clean visuals early on to create a definitive mood as well as sense of place. When things get more chaotic with handheld work later in the movie, and color begins to seep into things, it is unquestionably deliberate, and serves the more frantic third act well. On a technical level, about the only thing lacking is a good sound mix, for at times during the outdoor scenes (one in front of the Lincoln Memorial in particular) it’s a little too obvious that the dialogue was recorded in post.

Even so, these hurdles are manageable enough, and don’t present much of an obstacle to keep The Man Standing Next from accomplishing its mission. A slow-burn psychological odyssey through the mind of one man with the power to liberate a nation, the movie’s exploration of loyalty, duty, and honor ring out, and are aided in no small part by a tour-de-force performance from Lee. Opening today, The Man Standing Next might be a bit dense for those without any interest in South Korean politics or even late-1970s history, but for anyone fascinated by humanity’s struggle to maintain honor in the face of duty, it’s a must-see.

Comments on this entry are closed.