This review appears at Lawrence.com.

Words are Alice Howland’s life, yet lately she hasn’t been able to string them together to form meaning the way she intends. She is a linguistics professor at Columbia University, but she draws a blank during one of her lectures. She’s also getting lost during her runs and having trouble finding her way home.

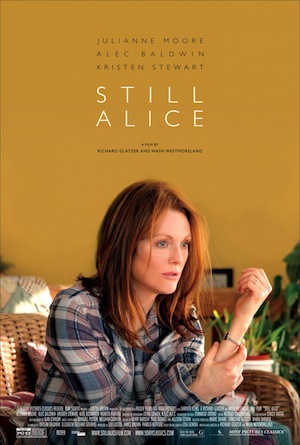

Alice, played by sure-fire Best Actress winner Julianne Moore with grace and humility, is 50 years old when she learns she has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Playing at Liberty Hall, Still Alice, which is adapted from Lisa Genova’s novel by writer-directors Richard Glatzer and Wash Westmoreland, is an affecting drama, blessed with two wonderful performances.

The movie casts a wider net up front, surveying the different reactions of Alice’s research biologist husband John (Alec Baldwin) and their three grown children. John is supportive and hopeful, but with a big career opportunity on the horizon, he exercises what might be considered his own selfish desires more often than not.

The irony, of course, is that even if he were to devote all of his time to Alice’s care, she wouldn’t remember it anyway. Baldwin never quite shakes his own person, but his struggle to remain sympathetic over his own bluster is well-suited to the role.

Alice is devastated but tries to remain realistic about her prospects. Her thoughts turn towards her kids (Kristin Stewart, Kate Bosworth, and Hunter Parrish) who, learning that it is hereditary, are all checked for signs of the disease themselves. Moore eschews histrionics, and her expressive face illustrates beautifully a woman who is very aware of the inevitable. She wants to stay connected to people for as long as possible, and then not put everyone through the heartache and trouble of having her not be present.

A young actress who skipped college against her mother’s wishes, Stewart’s character has the prickliest relationship with her mother, and Still Alice is at its best as that relationship develops in surprising fashion. In Adventureland and The Runaways, Stewart was able to stretch beyond the confines of the Twilight series, but here she shows reservoirs of understated emotion.

Glatzer’s diagnosis with ALS just weeks before the filmmaking couple began work on Still Alice gave the project some urgency. In the film’s plot, that urgency takes two forms—a grave decision Alice makes early on and a speech that she is scheduled to give at a conference. The speech is pretty obvious—unneeded proof of her determination and a reinforcement of more irony. The former works better as a suspense device because the film is full of moments that show Alice’s decline into dementia, each one ratcheting up the stakes. It’s believable that a woman of her conviction could make such a decision and stick to it.

But Moore is the real reason Still Alice works. She’s so natural and free of vanity. She doesn’t telegraph the tragedy of her situation like so many made-for-TV movies do. It’s a quiet performance and the uncertainty of how present Alice is undercuts everything, even the joyful moments.

Comments on this entry are closed.