A person has to tip their hat to a filmmaker who comes to the States, to the Sundance Film Festival, and presents a movie that straight-up indicts the U.S. government for a largely forgotten act of genocide. That’s precisely what first-time director Meul O. did this week with Jiseul, a drama about the 1948 South Korean uprising on the island of Jeju, a nightmarish event that claimed thousands of lives. And while it is definitely a freshman effort, and a little shaky in its historical foundation, Jiseul has more than a few moments of startling beauty and poignancy, and they carry the film through its lulls. (Jiseul also won Sundance 2013’s World Cinema Grand Jury Prize.)

A person has to tip their hat to a filmmaker who comes to the States, to the Sundance Film Festival, and presents a movie that straight-up indicts the U.S. government for a largely forgotten act of genocide. That’s precisely what first-time director Meul O. did this week with Jiseul, a drama about the 1948 South Korean uprising on the island of Jeju, a nightmarish event that claimed thousands of lives. And while it is definitely a freshman effort, and a little shaky in its historical foundation, Jiseul has more than a few moments of startling beauty and poignancy, and they carry the film through its lulls. (Jiseul also won Sundance 2013’s World Cinema Grand Jury Prize.)

Set on the South Korean island of Jeju, the film starts with text that explains how an American military order went out in 1948 that ordered all Koreans on Jeju living outside of a 5 km zone to surrender to the authorities or be labeled “communist,” a distinction that would see them summarily executed. Naturally, a number of villagers resist this order, and gather to plan their evasion of the South Korean soldiers sent to enforce the edict. This is where the film starts, out in the forest just outside of the town where the round-ups and executions are taking place.

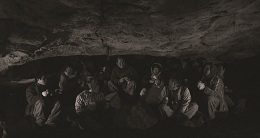

In this setting, a group of men slowly gather and crowd into a small foxhole, each of them hoping to (literally) lay low, and avoid detection by the authorities. It’s actually a somewhat amusing scene, and somewhat reminiscent of the famous Marx Brothers stateroom gag from A Night at the Opera. It is a very interesting way to start the film, for one of the primary themes of Jiseul is the basic human need to develop and maintain a community. These villagers crowding into the foxhole all have a long history with each other, as petty grievances within a small rural community are practically impossible to avoid. Yet as a cohesive group united by the bonds of persecution, they quickly find a common ground, and crowd together to make room for each other.

In this setting, a group of men slowly gather and crowd into a small foxhole, each of them hoping to (literally) lay low, and avoid detection by the authorities. It’s actually a somewhat amusing scene, and somewhat reminiscent of the famous Marx Brothers stateroom gag from A Night at the Opera. It is a very interesting way to start the film, for one of the primary themes of Jiseul is the basic human need to develop and maintain a community. These villagers crowding into the foxhole all have a long history with each other, as petty grievances within a small rural community are practically impossible to avoid. Yet as a cohesive group united by the bonds of persecution, they quickly find a common ground, and crowd together to make room for each other.

As the villagers retreat further into the forest, and find shelter in a small cave, the first sparks of a community begin to kindle as a casual, almost bawdy discussion about pigs, pregnancies, and local marriage arrangements allow the refugees a few moments to laugh off the severe danger outside. It’s an important moment, for it speaks to one of the central themes of Jiseul: humanity’s need for a personal, familiar connection. This point is made all the more poignant by the movie’s transition back and forth between the cave refugees, and the South Korean soldiers charged with their execution, for they are people too, people with the same basic needs.

Back in the village, these soldiers vary from innocent youths to the horribly sadistic, for while a few of them seem to take some sick pleasure in their grisly work, the majority appears understandably apprehensive about the standing order to kill all non-compliant civilians on sight. Two of these conscientious soldiers find each other and develop a bond, again bringing the community theme back to the fore. Indeed, even in the most grizzly circumstance, whether it’s hiding like a rat in a cave, or following abhorrent orders: people need to know they’re not alone.

Back in the village, these soldiers vary from innocent youths to the horribly sadistic, for while a few of them seem to take some sick pleasure in their grisly work, the majority appears understandably apprehensive about the standing order to kill all non-compliant civilians on sight. Two of these conscientious soldiers find each other and develop a bond, again bringing the community theme back to the fore. Indeed, even in the most grizzly circumstance, whether it’s hiding like a rat in a cave, or following abhorrent orders: people need to know they’re not alone.

Yet even with these palpable themes and engaging plot, Jiseul isn’t without its problems. The work of a first-time director, Meul O., it definitely has the feel of a freshman effort. The camera set-ups are largely uninspired, and hold on to a fixed, single-shot on a number of occasions where a slow pan or close-up would have helped provide agency to some of the group conversations. Shot in black-and-white, and lit modestly, there were a number of scenes where it was difficult to determine just who was talking. This also played into another disadvantage of the film, which was a lack of specific character development.

Thrown into the community of Jeju in the middle of the crisis, the audience is never really given a chance to get familiar with the characters before they’re lumped together into a dark-as-shit cave set. While certain characters do begin to take shape as the film goes on, especially the conscientious soldier, Private Park, and the cave group’s de facto leader, Yong-Pil, it’s hard to keep up with everyone’s story-line, and the personal dilemmas of each. And while there are flashes of promise in Meul O.’s camera moves (the lights fading on the cave group while their fire dies is especially clever), these moments come sporadically, and are overshadowed by a number of uninspired camera set-ups.

Something of a Sundance anomaly, Jiseul is an interesting film with a compelling, complete story that suffers from a lack of polish and technical pizazz. Most of the films that have left a middling taste in this reviewer’s mouth did so because they were almost entirely devoted to the look and texture of their movie, and less concerned with the working components of their incomplete story. This certainly wasn’t the case with Jiseul, which had an engaging narrative thread running through the picture from start to finish, yet didn’t seem quite mature enough to adequately take advantage of it.

Something of a Sundance anomaly, Jiseul is an interesting film with a compelling, complete story that suffers from a lack of polish and technical pizazz. Most of the films that have left a middling taste in this reviewer’s mouth did so because they were almost entirely devoted to the look and texture of their movie, and less concerned with the working components of their incomplete story. This certainly wasn’t the case with Jiseul, which had an engaging narrative thread running through the picture from start to finish, yet didn’t seem quite mature enough to adequately take advantage of it.

A decent first try, Meul O. will probably get another shot to do even better, if not in this country (the closing credits are even more antagonistic of U.S. foreign policy than the opening text), then perhaps in Korea. Citizen Kane, this is not, yet Jiseul has an interesting story, an important message, and lots of heart; indeed, it’s hard to trash any movie that comes to the table with all this in tow.

Comments on this entry are closed.