[Rating: Rock Fist Way Up]

An immersive exploration of gender, class, and the bonds of family set against the backdrop of 1970s Mexico, Roma manages to capture an essential collection of truths that span the gamut from micro to macro. Ostensibly the story of one housekeeper/nanny over the course of about a year, the film is able to transcend traditional narrative structures to speak about the ways people process happiness, grief, and hope. And while some may struggle with the movie’s lack of narrative momentum at times, those that look closer will discover that every frame of Roma is a calculated expression of what it means to be an invisible component in a larger world that would fall apart otherwise.

Roma opens in the house of a well-to-do Mexico City family whose carport driveway is being cleaned by their maid/nanny, Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio). Like so much of Cleo’s work, this too is just a temporary salve for people that always have something that needs cleaning, sorting, or minding. The dog keeps crapping on the driveway, the kids are constantly wreaking havoc around the house, and there’s always a cup of tea or plate of dessert that needs fetching. Yet Cleo is there for it all, and despite her position as a hired hand, she seems as much a part of the family as anyone.

Yet Cleo is very much on the outside, both figuratively and literally. She lives in a spare room outside of the house and above the carport where the dog craps, and is rarely allowed a free moment to exist as anything other than a domestic employee. Even when off the clock, she must abide by her mistress’ needs, using candles to light her room since even the electricity in the walls doesn’t belong to her. As Roma proceeds, the camera turns with slow yet deliberate purpose to take in this laborious existence that is at once desperate and beautiful: never moving so fast as to cast judgement or force the audience’s attention on any one thing.

And this is the axis upon which Roma spins, for it is a slice of life movie that lays out all the best and worst aspects of Cleo’s existence, often showing that these two poles are not necessarily exclusive. The mother of the family, Sofia (Marina de Tavira), is quick to scold Cleo for trivial matters that aren’t really her fault, but is just as quick to attend to Cleo’s medical needs when an issue arises. The kids are sometimes bratty, and strain the capabilities of their dedicated nanny, yet they are quick to smother her with a pure, genuine affection children are incapable of faking. It’s a tough, hardscrabble existence, yet at the same time it represents Cleo’s entire world, and the audience’s journey towards understanding why she wouldn’t trade it for anything serves as one of the main thrusts of the picture.

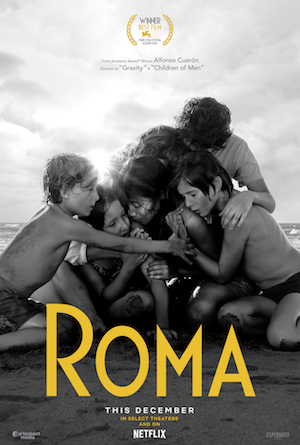

Alfonso Cuarón wrote, edited, shot, and directed Roma, which seems altogether appropriate since he’s made no secret about the film being a reflection of his own childhood experiences. There’s a deep and abiding affection for Cleo that runs through the film like a raging, overflowed stream, yet again, the movie never guides the audience toward any single conclusion or statement. Instead, it opts to let the world these characters inhabit wash over the viewers like the soapy water poured on the driveway. Fires burn, planes pass overhead, and protests pour through the streets, yet through it all Cleo moves on with a silent purpose that can’t be overcome.

There’s a narrative thread that tracks the family’s despair over the constant absence of the patriarch, along with another that follows Cleo’s turbulent relationship with a man, all with the ever-present political unrest of the nation percolating in the background. Cuarón seems more interested in the ways that his characters bake in this vast sociopolitical oven than the particulars of what each person or story build towards, which forms the basis for the theme of the film writ large: namely life as experienced by the invisible. This is a world whose reins are held by the women even if it is the men who are technically “in charge.” And amongst these women, it is the quiet, unassuming Cleo who wields the most influence, even if she possesses the least amount of power.

Aparicio is a revelation in the lead role, using her silence and body language as the sharpest tools in her acting armory. True to her social station as both a servant and a woman, she isn’t allowed much in the way of an opinion, which makes her performance in Roma nothing short of a revelation. The audience is never left wanting for understanding about what’s going on in her head, and while Cuarón is undoubtedly the painter, here, Aparicio is the brush. While Tavira does a magnificent job as the family matriarch, as do the children, the film just doesn’t work without this shattering turn from the rookie in the lead.

Roma is a stunning tour de force from a craftsman operating at the absolute peak of his game. Innocuous at first, and altogether unassuming, Roma will drop its roots into viewers if given the opportunity. From this unassuming seed grows a vast network of foliage whose branches spread beyond the base, covering a diverse array of themes that touch on class, gender norms, and what it means to live a full life. Guided by the invisible, and touched by the heretofore unseen, Roma is a journey into the heart of Cuarón, who has given over a part of himself with this. It is something to behold, and a testament to the enduring love hidden in an ugly world not prone to sentimentality.

Comments on this entry are closed.