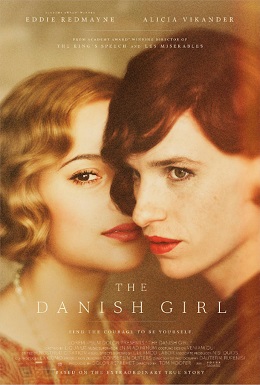

[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down]

Hollywood has come a long way in the last twenty-plus years as it concerns gay and lesbian recognition, respect, and celebration. In the 90s, films like The Birdcage, Philadelphia, and Gods and Monsters proved that decidedly non-heterosexual men and women could carry mainstream films, and paved the way for more ambitious fare in the 2000s. Trans culture has had a more difficult time finding a footing in Hollywood, and despite outstanding offerings like Boys Don’t Cry and Transamerica, both of them Oscar darlings, stories of transgender persons have had less cultural impact than a strictly L-G counterpart, like Brokeback Mountain.

The Danish Girl will almost certainly not reverse this trend, for despite compelling performances and a fascinating concept, the film fails to develop its characters, and plods along at a pace that almost dares the viewer to give up on the story. What’s worse, the movie often stumbles into outdated tropes about transgender people, and struggles to establish a narrative thread that connects a relatable character arc with the broader topic of trans culture exploration.

The movie starts at an art exhibit in 1926 Denmark, where celebrated landscape painter Einar Wegener (Eddie Redmayne) is fending off a small horde of well-wishers and fans. His wife, Gerda (Alicia Vikander), is quickly established as a supportive, loving partner who maintains an affectionate rapport with her spouse despite a lingering jealousy over his success and her lack of it as a portrait artist. Things change when Gerda loses her model one day, and asks Einar to pose in stockings, ballet shoes, and a dress so she might finish a piece. To both Gerda and Einar’s surprise, the session ignites a sudden and unexpected fire inside the man (along with a creative renaissance in Gerda). Although he seemed to have been functioning happily as a heterosexual male prior to the event, the unexpected portrait sitting changes everything for Einar, who later finds an excuse to go all-out, and wade into society as a fully accoutered woman.

Initially, Gerda encourages the “game” as they put it, yet as Einar continues to slip off his masculine identity so he can be “Lili” full-time, Gerda realizes that she is losing her husband. As Lili braves the intolerant world of 1926, and her struggle is indeed an exploration of admirable valor, the audience watches as the marriage between Gerda and Einar/Lili disintegrates while their bond of friendship and intimacy actually strengthens. Yet it is a laborious and sometimes tedious journey beset with very real and practical issues of pacing and character development (respectable work on both fronts is lacking).

And that’s a shame, for as already mentioned, Hollywood has not done the trans community a lot of favors over the years, with blockbusters like Crocodile Dundee still playing up the scary “gotcha” aspect of trans persons as recently as 1986. In that film, the main character, a somewhat naïve Australian bushman, encounters a trans person at a Manhattan bar, and is nearly seduced by the man passing as a woman. The main character’s “mistake” is only realized at the last moment, and the encounter is played up as a mildly frightening but humorous cautionary tale. This scene was par for the course for the majority of Hollywood’s existence when it came to trans men and women (see also, Bachelor Party), and is one the film community is only just beginning to buck.

The Danish Girl seems to suggests that Einar never felt any twinge of confusion when it came to his sexual orientation and identification prior to the portrait sitting, which only makes his sudden transformation into Lili that much more difficult to understand and relate to. What many LGBT people struggle with for a lifetime through puberty, adulthood, and sometimes even middle-to-old age passes for Einar in the course of a fast couple of weeks after a single cross-dressing incident. Although scenes early in the film show Einar to have a fleeting fascination with women’s clothes and fabrics, the core of his identity and sexual desires change almost overnight. Instead of an investigation into a life filled with struggles against personal and cultural expectations of the “norm,” the audience gets a detailed look at what a personal awakening looks like over the course of just a few rushed weeks.

This is not to discount the experience of any person who did indeed have a sudden personal and sexual awakening over the course of just a few days, yet to structure a narrative about a traditionally (in Hollywood, anyway) scary minority in such a manner threatens to dehumanize the trans community by alienating audiences sadly accustomed to the abrupt nature of this cinematic trope. The way the transformation into Lili is presented almost suggests that Einar caught his condition like a virus, and as events progress, and Einar is subjected to clinical diagnoses of insanity, the association lingers.

Despite Gerda’s understanding and moral support, not to mention Lili’s own courage, it is difficult to get behind Lili throughout most of the first half of the film, for she rushes headlong into an entirely new life with little thought to the consequences it will have legally, professionally, or on her existing marriage. What’s more, at times she pursues romantic connections with men before revealing the true nature of her identity, which brings the film back into Crocodile Dundee territory, if only by tangential means.

The timing, method, and means of a trans person’s decision to communicate the full nature of their sexual identity to a potential partner is something only that individual can consider and act upon. Yet again, since The Danish Girl doesn’t develop its characters in a before-and-after sense, and keeps Einar’s/Lili’s internal reasoning at arm’s length (the reasons Einar/Lili act the way he/she does is never really explored), it is difficult to connect with Lili. What’s worse, the fact that the film plays upon long-held notions of devious behavior amongst trans people only deepens the divide between audience and subject.

At nearly three hours, one laments the wasted opportunity, for there is ample time, directorial muscle, and acting horsepower to walk the line between cinematically engaging and broadly digestible. Yet The Danish Girl fails on both counts, and some of the best performances of the year by Redmayne and Vikander are the chief victims, along with a trans community that will have to wait a bit longer for a film that tells their story and connects with audiences.

Comments on this entry are closed.