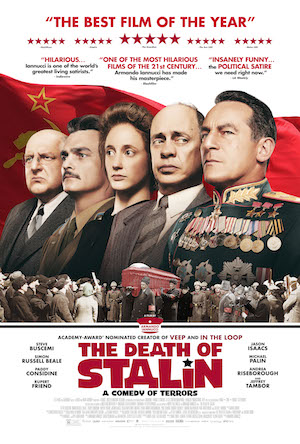

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

A political farce of the highest caliber, The Death of Stalin is equal parts funny and terrifying, and transcends what might have been a tonally treacherous minefield by leaning into the source-material’s real-life drama. Indeed, the myth of the Soviet Union’s socialist utopia always hovered just above the authoritarian terror laid into its foundation, and under Josef Stalin (Adrian McLoughlin), this ugliness was the great unspoken elephant in every room. Yet director Armando Iannucci once again demonstrates his flair for mixing political intrigue with high-stakes comedy, and ably juggles the life and death struggle of his story with historical drama that has never felt timelier.

As the film opens, the audience meets U.S.S.R. leader Stalin and his inner-circle, the latter of whom demonstrate a remarkable ability to turn mental cartwheels to stay in their boss’ good graces. Among the chief lieutenants are Malenkov (Jeffrey Tambor), Russia’s V.P. of sorts, Khrushchev (Steve Buscemi), one of the party’s highest-ranking politicians, Molotov (Michael Palin), one of the last surviving architects of the Revolution, and Beria (Simon Russell Beale), the head of the NKVD (Stalin’s personal Gestapo). Aware that any perceived slight or indiscretion could lead to their arrest and summary execution, these men choose their words carefully, and sleep with one eye open.

Everything gets turned upside down for them when Stalin falls gravely ill and dies, however. Long-running feuds and resentments have been building within this inner-circle for decades, after all, so everyone is acutely aware that whoever assumes the mantle of leadership will have scores to settle. Thus, in a matter of minutes, the political calculus changes, then changes again, and again. Depending on which way the wind is blowing, Malenkov, Khrushchev, Molotov, and Beria have to shuffle allegiances, alliances, and opinions so as not to be the last one without a chair when the music stops.

And so the film proceeds thus, with these men trying to navigate the ever-changing political landscape like someone trying to change the tire on a car going 50 mph. One person asks Khrushchev in mid-jog, “How can you run and plot at the same time?” and while this is just one amongst dozens of funny asides, it is also a telling scene that opens this world up a bit. This is a time and place where people are arrested and shot because they yawn at the wrong moment, or don’t clap long enough. Iannucci doesn’t flinch when touching on this, either, and makes a deliberate choice to show the horrors underpinning all of this humorous political tap-dancing.

This is important, too, because in a world where authoritarianism is on the rise again, it is vital that people familiarize themselves with the consequences of naked, unchecked, absolute power. Opinions not aligned with the great leader’s vision can be deadly in this reality, thus any semblance of representative government vanishes. After all, how can a politician represent their constituents if their one overriding goal in life is to stay in a leader’s good graces? This turns a person’s brain into a reptile’s: concerned wholly with survival, and the elimination of anything or anyone that stands in their way. The movie manages this balancing act between humor and violence well, never letting the importance of one outweigh the other as a crucial component of the narrative.

This is important, too, because in a world where authoritarianism is on the rise again, it is vital that people familiarize themselves with the consequences of naked, unchecked, absolute power. Opinions not aligned with the great leader’s vision can be deadly in this reality, thus any semblance of representative government vanishes. After all, how can a politician represent their constituents if their one overriding goal in life is to stay in a leader’s good graces? This turns a person’s brain into a reptile’s: concerned wholly with survival, and the elimination of anything or anyone that stands in their way. The movie manages this balancing act between humor and violence well, never letting the importance of one outweigh the other as a crucial component of the narrative.

Yet as good as the writing and directing is, The Death of Stalin succeeds largely because of the cast. Buscemi is as good here as he’s ever been, flailing around with a calculating desperation that is nothing short of revelatory. Palin is magnificent in the straight-man role as the cowed and whipped Molotov, who acts as a wonderful counterpoint to Beale’s headstrong Baria character. Better still is Jason Issacs, who comes into the movie well into the second act as famed Russian Field Marshall Zhukov, and all but steals the show with his swagger. Laughing off the palace intrigue surrounding him, Zhukov plainly states that after killing millions of Nazis, this political playground spat is nothing short of adorable to him.

Now, to be fair, The Death of Stalin does play a bit loose with the facts, albeit in a way that reasonably condenses the real history behind these events into a more digestible hour and forty-eight-minute serving. Without giving too much away, the film does indeed get the broad strokes of what happened following Stalin’s death correct, even if it speeds things up and (understandably) leaves out a few kangaroo court trials. It’s obvious that what matters to Iannucci is the interpersonal drama and humor born out of savage political desperation, and like his previous film, the superb In the Loop, he manages to find the funny in the seemingly mundane.

Now, to be fair, The Death of Stalin does play a bit loose with the facts, albeit in a way that reasonably condenses the real history behind these events into a more digestible hour and forty-eight-minute serving. Without giving too much away, the film does indeed get the broad strokes of what happened following Stalin’s death correct, even if it speeds things up and (understandably) leaves out a few kangaroo court trials. It’s obvious that what matters to Iannucci is the interpersonal drama and humor born out of savage political desperation, and like his previous film, the superb In the Loop, he manages to find the funny in the seemingly mundane.

Opening this week, The Death of Stalin is a hilarious yet sobering look at a massive power transition whose consequences reverberated not just within the Soviet Union, but across the globe. Although people might be familiar with Stalin as a historical figure, Iannucci’s film offers an uproarious look behind the iron curtain at the dramatized machinations of the men left in Stalin’s wake. And while it might be a laugh-a-minute, the picture is also a reminder of what awaits a country when it allows one person to indulge their worst impulses unchecked and unchallenged.

Comments on this entry are closed.