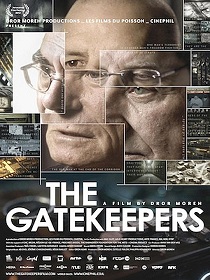

The Gatekeepers is the film that arrived at True/False with the biggest pedigree. As one of the Oscar nominees for Best Documentary, there’s a certain prestige that accompanies it. However, it wasn’t one I was terribly eager to see.

I’ve watched plenty of political issue documentaries, and while some of them are quite good, spending a couple of hours immersed in serious discussions about world-affecting issues isn’t really my idea of a fun Saturday. I expected a movie that was nothing more than an Israel-Palestine issue doc, one that came down with a heavy hand on one side of the conflict.

I couldn’t have been more surprised with the film I saw. Far from being preachy, The Gatekeepers is instead a fascinating, very smart look into one aspect of the never-ending global war on terror. The film consists of a series of interviews with six former directors of Shin Bet, Israel’s version of the CIA. Before this documentary, none of these men had ever been interviewed. Their activities remained a secret. Director Dror Moreh gets them all on the record about their counter-terrorism work, and the endless difficulties of the Israel-Palestine peace process.

The six men Moreh interviews are incredibly forthcoming with their information and opinions, especially given that they’d never talked about their work in public before. Unlike any current or former FBI or CIA director, these guys have no problem telling you exactly how they ran every operation during their leadership of Shin Bet, including the operations that didn’t go well. They don’t shy away when Moreh questions a decision, or goes somewhere uncomfortable. These are men who have had to make life-or-death decisions over very long careers, and are still living with the consequences of the choices they’ve made.

The six men Moreh interviews are incredibly forthcoming with their information and opinions, especially given that they’d never talked about their work in public before. Unlike any current or former FBI or CIA director, these guys have no problem telling you exactly how they ran every operation during their leadership of Shin Bet, including the operations that didn’t go well. They don’t shy away when Moreh questions a decision, or goes somewhere uncomfortable. These are men who have had to make life-or-death decisions over very long careers, and are still living with the consequences of the choices they’ve made.

No matter your opinion on the Israel-Palestine situation, The Gatekeepers is necessary viewing. It’s very impressive that a documentary about Israel’s intelligence-gathering organization comes off as neither pro-Israel nor anti-Israel. It’s a very human look at a complicated problem, and a group of men whose years on the job have given them lots of wisdom on the subject.

Some of the best screenings at True/False are the ones you stumble into by accident. Sure, there are always big-name films and festival darlings that everyone’s excited to see. But for every Gatekeepers there’s a movie you’ve never heard of that winds up being one of the weirdest, most interesting finds on the program.

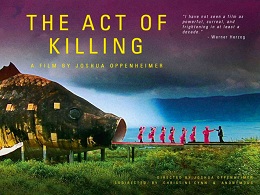

For me, The Act of Killing was that odd little surprise. It follows the lives of a group of Indonesian gangsters who were part of the wave of killings in 1965 and 1966 targeting branded “communists” (mostly ethnic Chinese) following the military overthrow of the Indonesian government. Because the gangsters in question were on the winning side of the coup, they’ve never had to face up to the atrocities they committed—unlike, say, the Nazis.

Director Joshua Oppenheimer takes it upon himself to bring about a bizarre kind of justice mixed with a social experiment. He works with the gangsters to create a film that re-enacts their crimes in violent detail. He talks to them about what they did, lets them pick out costumes and extras from among their friends and neighbors, and films scenes of violence and torture. Then he shows the men the footage and documents the results.

Director Joshua Oppenheimer takes it upon himself to bring about a bizarre kind of justice mixed with a social experiment. He works with the gangsters to create a film that re-enacts their crimes in violent detail. He talks to them about what they did, lets them pick out costumes and extras from among their friends and neighbors, and films scenes of violence and torture. Then he shows the men the footage and documents the results.

The Act of Killing presents its audience with some deeply unsettling subjects. The film’s main focus, a vain thug named Anwar Congo, appears at the beginning of the film to be like the devil himself. He’s charismatic, funny, and even seems sweet in his relationships with his grandsons and best friend (and fellow killer) Herman. But beneath that smiling exterior lies a man who has killed countless people, and appears to feel no remorse. Early on, he laughingly demonstrates the best way to kill a man without spilling too much blood. But the further in the film goes, the more the façade slips, and Oppenheimer shows Anwar as a man who’s truly haunted by what he’s done.

The Act of Killing is also accompanied by some crazy visuals that lend an additional trippy sensibility to an already strange setup. There’s a sequence illustrating Anwar’s nightmares, where ghosts of his victims come to kill him. There’s another scene where Anwar, Herman (in glittery drag) and a gaggle of pretty girls dance in front of a waterfall while “Born Free” plays in the background. In addition to its unique premise, this is a very visually distinct film.

The Act of Killing is also accompanied by some crazy visuals that lend an additional trippy sensibility to an already strange setup. There’s a sequence illustrating Anwar’s nightmares, where ghosts of his victims come to kill him. There’s another scene where Anwar, Herman (in glittery drag) and a gaggle of pretty girls dance in front of a waterfall while “Born Free” plays in the background. In addition to its unique premise, this is a very visually distinct film.

The movie does have a tendency to repeat its themes fairly often, and the lack of arc in any character that isn’t Anwar makes the film feel a bit overlong in places (though it comes in at a perfectly respectable two hours). It’s a problem that could easily have been fixed with some judicious editing.

Still, the visual highs and emotional payoffs contained within the film are well worth slogging through its slow patches.

Comments on this entry are closed.