F. Scott Fitzgerald opens his novel The Great Gatsby with the following passage.

“Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

I never received this advice from my own father, and even if I had, Baz Lurhmann has, for many years, had every advantage available, so my criticism can flow without restraint.

With his film version of The Great Gatsby, Baz Lurhmann creates a glittery and overstuffed adaptation that has all of the facts of the book right, while missing the skepticism and queries posed by its narrator and author.

With his film version of The Great Gatsby, Baz Lurhmann creates a glittery and overstuffed adaptation that has all of the facts of the book right, while missing the skepticism and queries posed by its narrator and author.

In the novel, Nick Carraway’s (Tobey Maguire) ability to reserve judgment allows him to stand in as an observer. The audience or reader can judge whether the characters with their affairs, lavish parties and impossible fantasies are beautiful or damned.

Lurhmann makes Nick too one-sided, and Tobey Maguire compresses him further, creating nothing more than a Jay Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio) fanboy. Lines such as “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life,” a line which Lurhmann uses almost word for word in his film, falls flat because the screen Nick is so obviously not repelled. There is nothing to balance the exaltation of wealth and excess.

To illustrate this point further, the scene that this line comes from takes place in the apartment that Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton) keeps for Myrtle Wilson (Isla Fisher), his mistress.

To illustrate this point further, the scene that this line comes from takes place in the apartment that Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton) keeps for Myrtle Wilson (Isla Fisher), his mistress.

Myrtle has invited a few friends over; one of them is Mr McKee (Eden Falk), a “pale, feminine man from the flat below.” Nick notices a spot of shaving cream on McKee’s face. This is a tiny yet important detail, because it appears in the film.

The afternoon drags into the evening and as the guests pass out from exhaustion or alcohol, Lurhmann has Nick engage in a flamboyant gesture to remove the bit of shaving cream. It’s used to accentuate the nature of the party and music. In the book the removal is more subdued.

The action is quiet, gentle and unnoticed by the others. Many have speculated about the sexual orientation of Nick Carraway because of this small yet rich passage.

This is what I mean when I say that Baz Lurhmann got the facts right and the content wrong. Revelers have surrounded Nick all day, and yet he has fixated on a small detail like the touch of shaving cream on a man’s face. Lurhmann puts the action in, but has made it a vulgar embrace of the party, and Nick’s own drunkenness.

This is what I mean when I say that Baz Lurhmann got the facts right and the content wrong. Revelers have surrounded Nick all day, and yet he has fixated on a small detail like the touch of shaving cream on a man’s face. Lurhmann puts the action in, but has made it a vulgar embrace of the party, and Nick’s own drunkenness.

This vulgarity extends to Lurhmann’s visuals. The use of 3D is tawdry and grotesque. It has all of the kitsch of 1970’s Saturday science fiction fare, but is so misplaced that you cannot help but be embarrassed for the director’s stupidity and lack of taste.

The technical needs of the 3D and highly composited shots also have another draw back. If you have watched a trailer for this film and wondered how you could be bored even though confetti and singers and jazz musicians are filling the screen it is because every shot must be controlled in such a way as to stifle the energy of each moment. There are no energetic, accidental, or serendipitous camera moves. There can’t be if the 3D is to work.

The technical needs of the 3D and highly composited shots also have another draw back. If you have watched a trailer for this film and wondered how you could be bored even though confetti and singers and jazz musicians are filling the screen it is because every shot must be controlled in such a way as to stifle the energy of each moment. There are no energetic, accidental, or serendipitous camera moves. There can’t be if the 3D is to work.

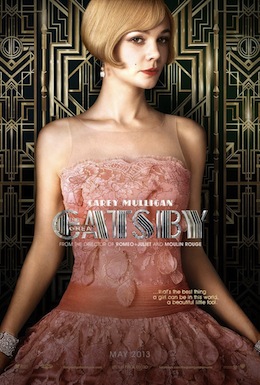

As for the acting, Carey Mulligan and Joel Edgerton are the only two standouts in the entire film. Mulligan occasionally falls victim to Lurhmann’s direction, but both she and Edgerton are able to make something of their characters in spite of the film. Leonardo DiCaprio and Tobey Maguire are not so lucky.

Though DiCaprio has a scene or two in which he’s able throw off Lurhmann’s bonds and make something of Jay Gatsby, for the most part his hopeful dreamer version of Gatsby is flat to off-putting. Maguire just seems like an after thought, and the idiotic framing device that Lurhmann places around the film, that of Nick writing the novel from an asylum, makes the character unworkable even for a good actor.

Though DiCaprio has a scene or two in which he’s able throw off Lurhmann’s bonds and make something of Jay Gatsby, for the most part his hopeful dreamer version of Gatsby is flat to off-putting. Maguire just seems like an after thought, and the idiotic framing device that Lurhmann places around the film, that of Nick writing the novel from an asylum, makes the character unworkable even for a good actor.

Since our film takes a literary bent this time around. I’d like to end with a moment from another work from the 1920s, that of In Our Time and more specifically “Big Two-Hearted River: Part II” by Ernest Hemingway.

Here another fictional Nick has just been out fly-fishing and has caught two trout. He cleans them and throws the guts up on shore, then rinses them in the stream.

Hemingway, you should have written this review of The Great Gatsby, because I couldn’t have said it any better. Baz Lurhmann has gutted Gatsby and though its color has not yet faded this cinematic version is hollow and dead.

{ 4 comments }

This is an amazingly dull film with far too much narration and no emotional weight. I even argue that Australia might actually be a better film.

Carraway actually DID say “They are a rotten crowd, you are worth the whole bunch of them put together.” That sums it all up. Then he said he disapproved of Gatsby all along, but that was because he didn’t know how much Gatsby truly loves Daisy, and hence instinctively, like all the others, get inclined to disapprove of someone who’s family background was secret, and like all the others who are all lost as to what the American dream, or simply meritocracy, is all about. At the end he realizes that although its not about birthright and classes, its not about money either, but hope, persistence and real love. There are three positions one can stand regarding their struggles – gatsby is a criminal and serves him right; the entire affair is morally ambiguous and that is the trouble of the american dream/ meritocracy; the american dream is a lie because people get increasingly morally irresponsible with wealth. I believe Nick stands in the third position. And even if he does not, there will be absolutely no value for a movie adaptation of the book to take the first two positions. The problem has not been solved, and people are still morally irresponsible everywhere in the so called meritocratic society. That is why Baz Lurhmann chose to portray the book in his manner. And I think the choice is impeccable.

And I would add that people who think otherwise probably have too many advantages to begin with, because anyone who cannot be moved by what Jay Gatsby has done would reveal himself as a downright bigot. Just like the guests who attended his parties, but was not to be seen in his funeral. What the hell, free booze every weekend, and they can’t spare 3 hours, or 2, to show this guy a modicum of respect? I’d say their only redemption lies in the fact that they are fictional! And they might be an exaggeration by fitzgerald, but precisely as such, it shows how much more the book is written in celebration of Gatsby.

The movie has a strong emotional weight alright, but that is precisely why it is laudable, and I hope that this movie can achieve what it sets out to do – persuade people towards moral uprightness, and that capitalism and money is only a means to an end, which is true love, the root of happiness.

Stanley,

It seems that you, like Lurhmann, missed the point. Nick’s disdain must be paired with admiration. He says a lot of things but rarely is anything to be taken at face value. Nick’s lack of judgment allows us to judge for ourselves in the book. Lurhmann’s adaptation is a reduction of the emotional complexities of the story. This is not to say simply that the book is better than the film, but the film could have been and wasn’t.

This story is not about true love. Gatsby is not in love with Daisy, but sees her as the final piece to his puzzle. Tom is what Gatsby strives to be (and never can be) and Daisy completes that journey. Daisy knows it cannot be which is why she doesn’t leave Tom.

Lurhmann tries to make it something of a love story, which is one of the many reasons why The Great Gatsby in his hands never works.

Comments on this entry are closed.