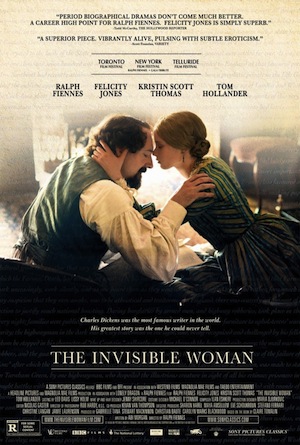

Two years ago Ralph Fiennes attempted a modern take on a Shakespeare classic. Fiennes’ second feature as director, The Invisible Woman, is a gauzy and beautiful period piece. It’s rich landscape, and speculation about the Charles Dickens’ (played by Fiennes) love affair with the young Nelly Ternan (Felicity Jones) is intriguing, but the film’s lack of a specific cinematic perspective leaves The Invisible Woman wanting.

Two years ago Ralph Fiennes attempted a modern take on a Shakespeare classic. Fiennes’ second feature as director, The Invisible Woman, is a gauzy and beautiful period piece. It’s rich landscape, and speculation about the Charles Dickens’ (played by Fiennes) love affair with the young Nelly Ternan (Felicity Jones) is intriguing, but the film’s lack of a specific cinematic perspective leaves The Invisible Woman wanting.

Fiennes’ film is based on the Claire Tomalin’s book of the same name. The story follows the probable relationship between Dickens and Ternan, who met during a production of Dickens’ play The Frozen Deep. Dickens was 45 and married, Ternan was 18.

The affair lasted from 1857 until Dickens’ death in 1870. It destroyed his marriage, but the strict Victorian social code and Dickens’ fame would not allow anything beyond estrangement from his wife. It absolutely would not permit any public acknowledgement of a relationship with Ternan.

There is limited evidence of the actual love affair between Dickens and Ternan. There is documentation of their meeting and rumors of the affair, but both Ternan and Dickens burned their letters to each other, leaving us to speculate about the details of their intimacy.

This allows a wide berth to any who care to suppose what might have been. Both Tomalin and screenwriter Abi Morgan craft a strong and stoic character in Nelly Ternan. The story also dabbles with Dickens’ indiscretions while never painting him as a flat villain.

This allows a wide berth to any who care to suppose what might have been. Both Tomalin and screenwriter Abi Morgan craft a strong and stoic character in Nelly Ternan. The story also dabbles with Dickens’ indiscretions while never painting him as a flat villain.

The problem with The Invisible Woman stems from Fiennes’ apparent unwillingness to place the camera in a position sympathetic to Ternan, and instead just gives us the too-easy silent omniscience of the unseen observer. This flattens the story and turns it into a tale of a powerful older man, using his every advantage to promote and maintain the adoration of a young woman. It’s a narrative that is so old and worn that it almost tells itself.

Fiennes could have explored the strength and character of Nelly, and he could have done so without changing a single scene or word of dialogue. He could have placed the camera in a position sympathetic to Nelly’s character, thus aligning the viewer with her. He could have created empathy instead of sympathy for Nelly, understanding instead of pity.

Fiennes could have explored the strength and character of Nelly, and he could have done so without changing a single scene or word of dialogue. He could have placed the camera in a position sympathetic to Nelly’s character, thus aligning the viewer with her. He could have created empathy instead of sympathy for Nelly, understanding instead of pity.

There is a particular scene that illustrates the ill-shot nature of The Invisible Woman. Nelly goes the house of Wilkie Collins (Tom Hollander), a friend and collaborator of Charles Dickens. Here she confronts Dickens about their relationship. Even in these moments, Nelly feels powerless, and it’s due in large part to how she is framed by the camera.

Perhaps Fiennes is trying to stay true to the title of his film, but The Invisible Woman shouldn’t be invisible to us.

Comments on this entry are closed.