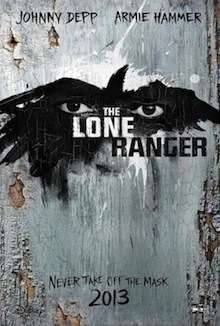

The Lone Ranger is a bizarre big budget summer movie for a lot of reasons. It’s based on a franchise most people are only vaguely aware of, yet director Gore Verbinski is oddly dedicated to honoring its source material and all of the staples that come with the icon. It’s a gritty Western revenge story that gets as close to an R-rating as it can. It’s also a screwball, buddy comedy between Armie Hammer and Johnny Depp as The Lone Ranger and Tonto, respectively. It dabbles in Native American ghost story, comments on the corruptibility of capitalism and stops off long enough to mention the plight of the Native Americans and Chinese immigrants during Western expansion.

The Lone Ranger is a bizarre big budget summer movie for a lot of reasons. It’s based on a franchise most people are only vaguely aware of, yet director Gore Verbinski is oddly dedicated to honoring its source material and all of the staples that come with the icon. It’s a gritty Western revenge story that gets as close to an R-rating as it can. It’s also a screwball, buddy comedy between Armie Hammer and Johnny Depp as The Lone Ranger and Tonto, respectively. It dabbles in Native American ghost story, comments on the corruptibility of capitalism and stops off long enough to mention the plight of the Native Americans and Chinese immigrants during Western expansion.

The problem is, it doesn’t do any of these things particularly well.

Oddly enough, Hammer plays said ranger in this origin story (oh yeah, it’s that too) a lot like a Disney version of Depp’s character from Dead Man. Out of his element in the West, he returns to his home town an educated man with a deep appreciation for the law. Of course his Texas ranger brother, played by James Badge Dale, has a different view of the law and how to enact it. Naturally, something happens that changes Hammer’s character, and he puts on the mask to become an outlaw that rides for justice.

The first action scene works well as a metaphor for the movie as a whole. A complex, daring-do train heist that eventually caves in on itself, we’re introduced to our two protagonists, as well as one of the movie’s villains, a nearly unrecognizable William Fichtner. It’s an explosive, long-winded scene

that ends with a level of chaotic destruction that even Michael Bay would appreciate. It also establishes that our heroes are nearly indestructible in this universe, as they are able to leap from a derailed train, tuck and roll, and emerge relatively unscathed.

Verbinski is a talented action director when he remains focused and there are some fantastic moments in The Lone Ranger, particularly early on during a violent ambush. On more than one occasion, he pushes what can be allowed in a PG-13 movie about as far as he can. Unlike other big summer movies that go for coveted rating, Verbinski nearly insists on showing the repercussions to the violent things many of these characters do – as long as it’s not the leads who have to experience it. Gunshots yield blood. Knives cleave skin. Hearts are eaten (seriously). Even more abstract repercussions like guilt land some characters. The Lone Ranger is a quietly responsible movie at times.

Verbinski is a talented action director when he remains focused and there are some fantastic moments in The Lone Ranger, particularly early on during a violent ambush. On more than one occasion, he pushes what can be allowed in a PG-13 movie about as far as he can. Unlike other big summer movies that go for coveted rating, Verbinski nearly insists on showing the repercussions to the violent things many of these characters do – as long as it’s not the leads who have to experience it. Gunshots yield blood. Knives cleave skin. Hearts are eaten (seriously). Even more abstract repercussions like guilt land some characters. The Lone Ranger is a quietly responsible movie at times.

But it also goes the other direction into pointless excess. One scene sees an entire tribe of Comanche murdered just to establish that a character is a bad guy. Another serves to highlight the town’s distrust and hatred of Native Americans, only to devolve into a series of pratfalls. It’s as if the movie makes a nervous joke, anytime it gets to close to something heavy. The scene featuring the slaughtered Comanche is bookended by the ranger’s horse, Silver, inexplicably stuck in a tree. Not all of the humor is bad in The Lone Ranger, but enough of it is, that Verbinski and company should have just played it straight or used Tonto as a straight man instead of a one-liner machine.

There are some bright spots in The Lone Ranger, to be sure. Fichtner performance is terrifying. Maybe it’s because he’s able to hide behind a pretty convincing prosthetic, but his character Butch Cavendish, is one of the most intimidating, frightful villains of the summer. But the film’s highlight is its final action sequence, which features the heroes and villains trading gunfire and barbs across two adjacent trains. It skillfully pairs and unpairs characters, as they move from one train to the next and it moves briskly to a satisfying end. Most important of all, it’s fun.

There are some bright spots in The Lone Ranger, to be sure. Fichtner performance is terrifying. Maybe it’s because he’s able to hide behind a pretty convincing prosthetic, but his character Butch Cavendish, is one of the most intimidating, frightful villains of the summer. But the film’s highlight is its final action sequence, which features the heroes and villains trading gunfire and barbs across two adjacent trains. It skillfully pairs and unpairs characters, as they move from one train to the next and it moves briskly to a satisfying end. Most important of all, it’s fun.

In all, The Lone Ranger is a mixed bag, but it really just needs an edit and a decisive tone. Had it been 30 or 45 minutes shorter and more focused, it would have been a different film entirely.

Comments on this entry are closed.