[Minor Rock Fist Up]

Hype is a strange thing. It can create anticipation or it can just as easily wear you down. In this case, I found myself adjusting expectations on an almost scene-by-scene basis.

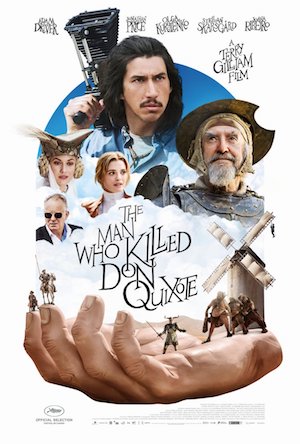

It took more than a decade for writer-director Terry Gilliam to get his first production of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote off the ground. He eventually began filming his off-kilter pseudo-adaptation of Cervantes’ classic novel Don Quixote in 2000, with stars Johnny Depp and Jean Rochefort, but extreme weather conditions and an injury to Rochefort stopped filming dead. A documentary about the making of that ill-fated production surfaced in 2002, and it took 15 more years to re-start a legit production. Almost three decades in the making, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote finally releases with a re-worked script and Adam Driver and Jonathan Pryce in the lead roles.

Watching the movie now, one can’t help but see it through the lens of Gilliam’s own personal obsession, viewing it as a sort-of autobiographical, self-fulfilling prophecy. The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, it turns out, is about the hubris of being an artist — a filmmaker, in this case. The story begins with a young advertising hotshot named Toby (Driver) preparing to shoot a commercial in a rural Spanish village, the same location where he made a student film a decade earlier and ruined the lives of the townspeople (including Pryce’s simple cobbler, Javier) by promising them the stars. Though he once saw himself as the chivalrous knight who would save the town, Toby is now selfish and disillusioned (a trope Gilliam used to great effect in Monty Python and the Holy Grail as well). The town has changed, too. Javier is ensconced in an illusion, and the village is a shell of its former self. Toby’s increasingly unhinged perception of events combines with Javier’s flashes of delusion to undermine and intrude on reality.

Pryce is perfect — a mix of vulnerable, heartbreaking and hilarious. His slapstick moments work within the madness, but the ones with Toby’s boss’ sex-crazed wife (Olga Kurylenko) are woefully miscalculated. In general, the female characters are painfully one-dimensional and attitudes toward them are more of the virgin/slut variety. Driver has a tougher road to his character’s “waking up” and the script hasn’t calibrated it correctly, but he plays it well and carries the audience through the rougher patches.

Behind the camera, Gilliam’s usual Dutch angles and wide-angle lenses are used in Toby’s student film, not the rest of the story, which seems to be Gilliam’s way of commenting on the maturity of the artist, and even his own films. Surprisingly, the surreal qualities of the movie are functions of the script more than the camera. The “reality” storyline is so increasingly hard to buy that it makes the whole film seem hallucinatory even without the crazy angles. Viewers hell-bent on figuring out exactly where each begins and ends will be frustrated – and maybe that’s the point.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote begs us to let go. And when you do, you realize that Gilliam’s vision coalesces more as the movie progresses. Filmmakers are dreamers, after all, and reality sucks, so who wouldn’t want to be caught up in delusions of grandeur every now and then to make life more bearable?

This review is part of Eric Melin’s “LM Screen” column that appears in the upcoming summer edition of Lawrence Magazine.

Comments on this entry are closed.