Paul Thomas Anderson established himself early in his career as a capable director, often drawing comparisons to Robert Altman for his large ensemble pieces and Jean Renoir for his moving camera and long, meticulously choreographed follow shots. He has garnered critical acclaim throughout his career, but after the somewhat tepid public reception of Magnolia, he followed it with a lighter, less challenging movie, Punch Drunk Love.

Paul Thomas Anderson established himself early in his career as a capable director, often drawing comparisons to Robert Altman for his large ensemble pieces and Jean Renoir for his moving camera and long, meticulously choreographed follow shots. He has garnered critical acclaim throughout his career, but after the somewhat tepid public reception of Magnolia, he followed it with a lighter, less challenging movie, Punch Drunk Love.

With There Will Be Blood, he effectively transitioned from a gifted, independent voice to a fully-formed auteur, capable of telling his own stories the way he wanted to tell them. There is little compromise in that film and it’s all the stronger because of that. Now, with The Master, Anderson has moved even further into the realm of uncompromising artist. His skills as a visual storyteller continue to advance, his ability to confront abstract ideas and universal themes is further honed and his technical mastery of the principal elements of filmmaking create film that is singularly and holistically outstanding.

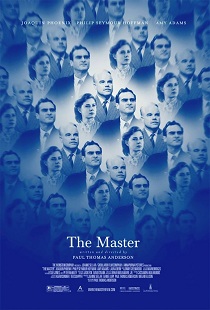

The Master is anchored by a pair of tour de force performances from Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix. The former plays Lancaster Dodd, a boisterous would-be prophet who holds council with some private, wealthy socialites. The latter plays Freddie Quell, a veteran of the Korean War, who has returned home, but hasn’t successfully re-entered civilian life.

The film forgoes clearly drawn plot points and beats, instead choosing to spend its time on relationships between the characters and the greater themes of faith, religion and manipulation. The Master runs at a brisk pace, but its narrative is dense and definitely benefits from discussion and multiple viewings. The film ends in a whisper, but the ripples it makes in your mind last long after viewing.

The film forgoes clearly drawn plot points and beats, instead choosing to spend its time on relationships between the characters and the greater themes of faith, religion and manipulation. The Master runs at a brisk pace, but its narrative is dense and definitely benefits from discussion and multiple viewings. The film ends in a whisper, but the ripples it makes in your mind last long after viewing.

Anderson has always had an affinity to draw great performances from so-so actors, but when given high-caliber talent such as Daniel Day Lewis in There Will Be Blood, the performances he’s able to summon are revelatory. The same is true here. Hoffman’s prophet is magnetic and fully formed. Hoffman disappears into a character that is boisterous, angry and, above all, charismatic. His mannerisms and presence are natural and unnerving.

In a lesser film, Hoffman’s performance would overshadow the other actors, but he is met with equal unhinged talent by Phoenix, whose drifter is volatile, dangerous and deeply, deeply disturbed. These actors have the kind of chemistry together that most actors work their entire careers to achieve. And while much of their time is spent in muted evaluation of each other, there are times where they are allowed to show their true nature and those scenes are joyous.

And that’s The Master as a whole. It’s quiet, muted at times, as Anderson says with a single shot what lesser directors spend entire scenes on creating, and it ends on a vague whimper. But whether the film is directly engaging its themes and its characters’ struggles within the film’s world, or working toward something more abstract, the journey is beautiful one. And deserves to be taken again, and possibly again. The Master is masterful.

Comments on this entry are closed.