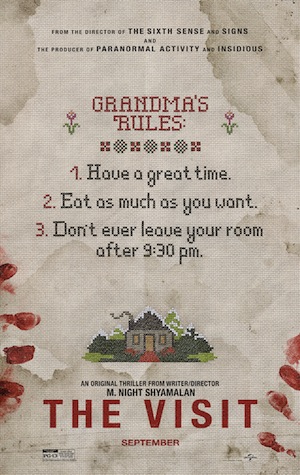

There is no compelling reason for you to have any faith in M. Night Shyamalan. For years he has abused the trust that he garnered with The Sixth Sense with regrettable offerings such as The Happening and After Earth.

I understand if you decide to ignore me when I tell you that his new film The Visit plays on the strengths of earlier films like The Sixth Sense or Unbreakable. Shyamalan does not deserve your trust, but that does not mean The Visit is a completely unworthy film.

Becca (Olivia DeJonge), a media savvy 16-year old, and her 13-year-old brother, Tyler (Ed Oxenbould), go to visit grandparents, Nana (Deanna Dunagan) and Pop Pop (Peter McRobbie), whom they have never met. Becca decides to document the entire visit to create a documentary, which she hopes might heal her mom’s (Kathryn Hahn) estrangement from her own mother and father.

When the two adolescents arrive, they discover that their grandparents may not be in a particularly good mental state, which quickly shifts from amusing to troubling.

The conceit of a 16-year-old creating a first person documentary and her overwhelming commitment to the task is only half believable, but if you can accept the framing device, it creates moments of solid visual suspense. Shyamalan relies on what you know to be just out of sight, but present to build anticipation. We know something strange is going on, but it is always just out of view, around the corner, out of frame. When something then moves into view, even though we expect it, it surprises us.

The secluded space of a farmhouse, a cinematic horror standard as old as the unseen threat, adds to the vulnerability of the grandchildren.

The secluded space of a farmhouse, a cinematic horror standard as old as the unseen threat, adds to the vulnerability of the grandchildren.

I should mention that The Visit is intended to be a horror comedy, and though the precocious Tyler who fancies himself a rapper is tiresome at best, the incongruence of wired teens and disconnected rural grandparents does work for the most part.

The most satisfying laughs parallel the most satisfying scares. They are the ones built on an understanding of framing and narrative cinematic fundamentals. These humorous situations comment on the same visual devices that scared us just moments before.

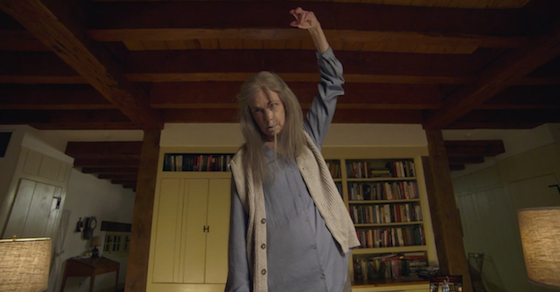

On the second or third night of their stay, Becca and Tyler hear a banging in the hallway. They already know that Nana is suffering from sundowning, which causes eradicate and confused behavior at night, but the noises are so worrisome that the teens feel compelled to open the door. The camera peers into the darkness. Nothing seems amiss, and just when we are about to settle into complacence, the nightgowned Nana runs through the frame, a spectral blur in the otherwise black hallway.

In the next scene, the grandkids are now outside taking a daytime walk with their grandparents in the nearby woods. Tyler turns to Becca, who is still following with her camera, and asks her to guess who he is. Tyler then begins dashing from off camera on one side of the frame to the other. A direct visual reference to what caused the viewer tension, now, in the daylight, causes uproarious laughter.

It is a joke that works on multiple levels. It is visceral and direct, since we’ve just seen what Tyler is making fun of, and it also works likes a cinematic inside joke. It is a wink and a nod to the visual construction that has been employed in motion pictures for almost a century.

The performances of Peter McRobbie as Pop Pop and Deanna Dunagan as Nana also deserve praise. Often the nuance of their performance within a scene, the shift from mentally present and warm to distracted and threatening, is the substance that gives the scene its disconcerting power.

The performances of Peter McRobbie as Pop Pop and Deanna Dunagan as Nana also deserve praise. Often the nuance of their performance within a scene, the shift from mentally present and warm to distracted and threatening, is the substance that gives the scene its disconcerting power.

The viewer, because of the performances from McRobbie and Dunagan, are sympathetic yet hesitant about both grandparents. Dunagan is particularly affective in her portrayal of Nana.

Shyamalan still succumbs to his penchant for the overly sentimental, and is too reliant on more exposition than any viewer would need. The bookends to The Visit, which feature a confessional like conversation with Becca and Tyler’s mother, are a disaster. It’s unfortunate that Shyamalan could not have shown better critical sensibilities when editing these parts of his screenplay.

If you are a glass half full person, you might say that these bad habits don’t work to inhibit the fun which The Visit can offer. If you are more glass half empty, an attitude that feels more comfortable to me, then you can point to the moments of cinematic competence, and ponder at Shyamalan’s enduring inconsistencies and need to tell the viewer exactly what emotions his characters are feeling.

If you are a glass half full person, you might say that these bad habits don’t work to inhibit the fun which The Visit can offer. If you are more glass half empty, an attitude that feels more comfortable to me, then you can point to the moments of cinematic competence, and ponder at Shyamalan’s enduring inconsistencies and need to tell the viewer exactly what emotions his characters are feeling.

It may not be a ringing success, but it is also far from a complete failure. It may just be the first film from M. Night Shyamalan in a very long time that you should go and see in the theater.

Comments on this entry are closed.