[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

In Theaters Friday, September 6

Some people identify a short temper, a love of the outdoors, or a predilection to art with their upbringing, while other people must contend with the fact that their parent(s) happened to be clinically insane and created an alternate reality for a young person in their most critical developmental stage. Hoard explores the emotional scars scratched into both the inside and outside of people, groping around for a kernel of truth amidst the kaleidoscope of colors that shade the bruises of generational trauma.

Set in two phases, Hoard starts with Maria (Lily-Beau Leach) at about 8 or 9 years old in mid-1980s London. Although she goes to a school where the students and faculty mock the young girl for her shabby appearance and absent-minded ways, her “real” world is the one her mum (Hayley Squires) spins to life via a collection of songs and rituals only the two of them understand. Part of this private world involves a dangerous level of hoarding that at once reflects a mother’s love (scavenging every available resource for a child’s upbringing), but also her sickness (their apartment is a putrid, rotting collection of items not at all safe for habitation).

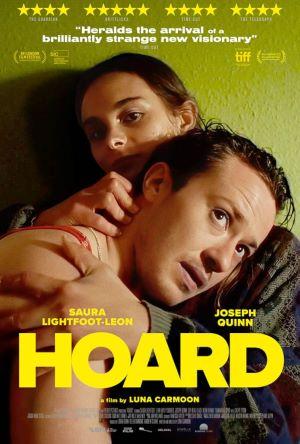

An accident leads to a call to England’s version of social services, with Maria in foster care thereafter. A time jump about 10 years into the future finds young-adult Maria (Saura Lightfoot Leon) on her last day of school without even a single clue about what to do with herself. Still living in the same group home that originally took her in, she finds herself drawn to another former foster kid who returns to the house to check in on their shared/adopted mother. Michael (Joseph Quinn) is “nearly 30,” yet he and Maria begin a flirtatious relationship rooted in shared trauma and abandonment issues: one that sees them both outwardly regressing.

It’s a fascinating journey through young adulthood and is given depth by the layers added to Maria as a character in both phases of her story. Although the adult version seems to find comfort in the memories of her youth, scenes early in the picture show that she also had a difficult time reconciling her life with what she saw all around her. At one point young Maria says to her mother, “I’m ashamed of us. I hate what we are.” Yet as Maria and Joseph begin to circle each other and the stress of adulthood reactivates old memories and wounds, the young woman begins to find comfort in the rituals associated with her chaotic and unorthodox upbringing.

Writer/director Luna Carmoon uses phrasing and situational callbacks to connect the two halves of Maria’s story both for her and the audience. Certain phrases (“rat-king”), items (chalk), and even actions (food fights) reconnect Maria with memories and trauma that she’s spent half her life overcoming. How Maria grapples with the complicated nature of her childhood, along with her complex and conflicting feelings about it, inform the back half of Hoard, and the journey of that discovery doesn’t progress so much as it unspools.

Maria and Michael’s connection sees them both reverting to an almost primal state where they can strip away the walls that structured society has demanded of them, and Lightfoot and Quinn sell the hell out of it. Although liberating for a time, their performances demonstrate how this new relationship also brings both closer to the trauma that those same walls protected against, and invites a reckoning that forces some difficult introspection. For many people, this young adulthood moment invites ideas about a career to take up, or a guide to parenthood informed by their upbringing; for Maria and Michael, this becomes is an internal confrontation about who they are (and a dangerous one considering their histories).

Stellar lead performances aside, Carmoon doesn’t quite nail the pacing of the story, with nearly 50 minutes passing before the movie gets out of its first act. This extra time establishes Maria’s trauma well, but leaves precious little for the narrative’s overall development during the back end. Certain scenes linger beyond their function in the story, and while they add color to the world and the ancillary characters, they often feel less like a functional piece of the story and more like something pulled directly out of Carmoon’s own memories. Much of this is necessary early on as foundational text for what Maria must battle as an adult, yet at 126 minutes, Hoard feels one more edit and 15 excised minutes away from something truly special.

A sometimes uncomfortable watch that nevertheless squeezes every possible ounce of drama out of the squirms it induces, Hoard succeeds in what it sets out to do. A story about the childhood wounds that never completely heal and the triggers that threaten their reopening, the film’s use of a frantic relationship as a framing device in the second half further develops an arguably too-long first act that still packs a hell of a punch. 10/10 performances from all the principles bolster what is occasionally a tedious exercise in memory therapy for Carmoon, who has laid herself bare at the alter of cinema with this one.

Comments on this entry are closed.