This review originally appeared on Lawrence.com.

This review originally appeared on Lawrence.com.

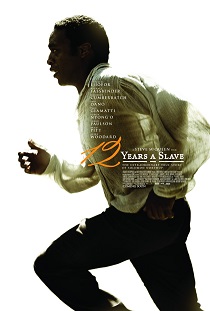

Make no mistake, 12 Years a Slave is a horror movie, even though it doesn’t traffic in the kind of otherworldly storytelling that the horror genre is known for.

The acclaimed film is based on the 1853 first-hand account of a black free man named Solomon Northup who was kidnapped in 1841 and sold into slavery. Directed by British filmmaker Steve McQueen, 12 Years a Slave turns the audience into voyeurs with an unblinking gaze that is truly terrifying.

Chiwetel Ejiofor plays Northrup, and the story unfolds through eyes as he is witness to — and subjected to — countless cases of inhuman behavior. Even though it’s told from Northrup’s limited perspective, the movie covers a wide spectrum of institutionalized cruelty and achieves a sweeping portrait of our nation’s great shame without the traditional sweeping scope that a big-budgeted epic would have.

Brutality is thrown into sharp relief from the outset, as Northrup is chained up and beaten with a plank of wood over his back until it breaks — and his kidnapper picks up another one. The camera looks up from a low angle with a clear view of Ejiofor’s face and the obvious relish of his attacker, while the soundtrack emphasizes the full force of the attack. The sound design throughout the movie is often jarring — blunt impact, rushing water, open sobbing — especially in early montages of Northrup’s captivity.

His initial outrage at being treated like a slave gives way to a sense of helplessness that carries throughout the entire picture. There’s little sentimentality here, but it’s heartbreaking to see how Northrup’s outlook is recalibrated as he endures his new life. Plantation owner William Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch) almost treats him with something approaching respect, but it’s clear that in the end, Northrup is still property.

His initial outrage at being treated like a slave gives way to a sense of helplessness that carries throughout the entire picture. There’s little sentimentality here, but it’s heartbreaking to see how Northrup’s outlook is recalibrated as he endures his new life. Plantation owner William Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch) almost treats him with something approaching respect, but it’s clear that in the end, Northrup is still property.

The relationship between master and slave is dissected organically from nearly every possible side, especially with the introduction of the stellar Michael Fassbender as an abusive, alcoholic planter and his wife (Sarah Paulson), who is threatened by her husband’s attraction to a slave girl named Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o).

Northrup’s interaction with other slaves is even more complicated. Again steering away from easy sentimentality, he lectures a woman who’s been separated from her kids to curtail her obvious grief. The nonchalant way that his fellow slaves go about their day in a life-threatening moment for Northrup is quietly devastating.

McQueen’s approach is not the pure naturalistic one you might expect, considering the hard-edged subject matter and his predilection for gritty stories such as Hunger and Shame, his previous two films. There’s plenty of cinematic virtuosity on display — including long takes, impressionistic editing and point-of-view camera movement — that help create a more vivid experience.

McQueen’s approach is not the pure naturalistic one you might expect, considering the hard-edged subject matter and his predilection for gritty stories such as Hunger and Shame, his previous two films. There’s plenty of cinematic virtuosity on display — including long takes, impressionistic editing and point-of-view camera movement — that help create a more vivid experience.

The concealment of his intellect and education provide a fascinating internal struggle, one which Ejiofor balances beautifully with his character’s basic survival instincts. It’s equally painful for him to endure abuse or be a spectator, as he often is. So are we. In one key scene, the eyes that have witnessed such horror turn slowly from the sunset and directly to the screen, as if he’s looking directly at us.

Through a rich, grueling portrait of the machinery of institutionalized slavery, McQueen asks us to examine the rotten core of slavery and how it permeates our entire culture, not just to ponder life as it was in the 1840s.

{ 2 comments }

Good review Eric. While I didn’t love this one like everybody seems to, I definitely respect it as a movie that deserves to be seen by any and all people who need a brutal, clear-view of slavery.

I was really impressed by the fact that it avoids the obvious sentimental places it could have easily gone to. For a subject this brutal and emotional, it didn’t need cloying sentimentality and it’s better for it.

Comments on this entry are closed.