[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

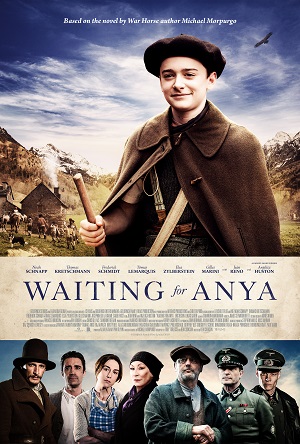

A coming of age story about a boy named Jo who shelters Jews while living under Nazi occupation, one can’t help but to feel bad for director Ben Cookson and his new picture, Waiting for Anya.

Cookson couldn’t have known that his movie would be released only a few days before a film about a boy named Jojo, who shelters a Jew while living under Nazi occupation, would compete for a handful of Oscars, yet sometimes that’s just how things shake out. The similarities between the two films are mostly surface level, however, and create enough distance between the plots and characters to make for wholly distinct stories that stand well enough on their own.

Waiting for Anya opens with onscreen text setting the story in 1942 France, where a man and his young daughter, both with Stars of David stitched onto their coats, are being directed towards a waiting train. The man, Benjamin (Frederick Schmidt), makes a daring move to escape deportation, but must hand his young daughter off to a stranger, one he hopes will assist the girl and get her to the south where he intends to meet her. The film then fades out and back into the small village of Lescun, where a 14-year old boy named Jo (Noah Schnapp) is tending to his family’s sheep herd while narration from an older man sets this up as his (Jo’s) story, told decades later.

Jo and his flock are startled by the appearance of a bear, which leads the young shepherd to Benjamin, who has been hiding in the woods outside of town. It turns out Benjamin’s mother-in-law, the local widow Horcada (Anjelica Huston), has been sheltering Jewish children and guiding them across the Pyrennes Mountains to safety in Spain. The pair are still waiting on the arrival of Benjamin’s daughter, Anya, yet there’s plenty of work to be done with the other kids in the meantime.

Although promised to little more than silence at first, the arrival of a German garrison in Lescun motivates Jo to do more, and he enlists in the community’s resistance network to aid in the protection of the Jewish children. As the film progresses, Jo is confronted with a number of difficult decisions and shades of morality that challenge his understanding of the world around him, and rush the young man towards an adulthood that seemed far off at the beginning of the picture.

The script for Waiting for Anya is an adaptation of the book of the same name by Michael Morpurgo, who also authored War Horse (adapted into a 2011 film). Both movies share a restrained tone that frames the action for a younger audience, keeping the horrors of war at arm’s length for the most part. Although the phrase “concentration camp” is indeed mentioned in Waiting for Anya, the threat that the children hiding in Lescun face is nebulous in nature and remains mostly unseen. The Nazis that arrive in town are vaguely menacing and serve a purpose for the conflict of the narrative, yet the film never concerns itself with establishing a broader scope for their cruelty.

On the one hand, this seems somewhat appropriate, for southwestern France in 1942-1944 was far enough away from Normandy and the Falaise Pocket that a sleepy village like Lescun could have been ignorant of the horrors taking place in Russia and Poland. Yet the film offers a number of characters like Benjamin who know enough to communicate just how bad things are, and while Waiting for Anya does touch upon the dangers the Germans represent, it remains largely in the background.

This sanitized approach to the period is also reflected in the costuming and set design, which eschews period and place-specific authenticity for a clean and sharp visual aesthetic. Everyone’s clothes look freshly washed, pressed, and smartly assembled despite the main characters living in a farming community, yet even this seems to be a deliberate choice. There are several sweeping vista shots that interrupt the narrative to drink in the rolling green hills, majestic mountain ranges, and crystal-clear streams littering the region, setting this tale up as something of a rose-tinted memory as told by the film’s narrator.

So, in a thematic sense, these visual and tonal decisions are appropriate and consistent with the kind of story Cookson is trying to tell. Sure, comparisons to Taika Waititi’s Jojo Rabbit may be inescapable, yet the pictures operate on different frequencies and are clearly positioned in separate genres (not to mention adapted from books written decades apart). And while the main characters might share the same name, deal with similar dilemmas, and even have sympathetic Nazi friends (Thomas Kretschmann essentially reprises his role in The Pianist, here), Waiting for Anya is hardly a knock-off.

Schnapp does a decent job in the lead and bears the emotional weight of the character well, and he’s aided in no small part by Huston and Jean Reno, the latter of whom plays Jo’s grandfather. The story doesn’t take a lot of risks, yet the pacing of the effort is tight and keeps things moving along at a good clip throughout the 110-minute runtime. A World War II Holocaust-adjacent film that’s appropriate for the whole family, Waiting for Anya might not carry the emotional or intellectual weight of its cinematic cousin Jojo Rabbit, yet it succeeds on its own merits by keeping the story contained to a handful of sturdy characters that are well positioned, acted, and explored.

Comments on this entry are closed.