[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Down]

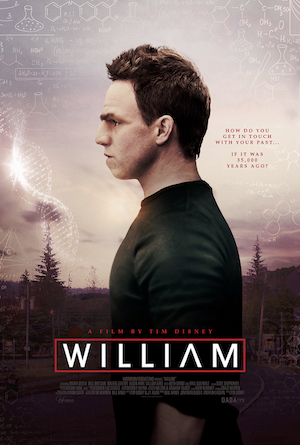

A heavy-handed morality tale wrapped in a slick, polished film, William never manages to push past the predictable beats of its genre’s predecessors, and stumbles further when it tries to parlay its themes into child-rearing messaging territory. The story of a 21st-century Neanderthal clone coming of age in a world that’s leap-frogged him on the evolutionary chart, the new film by director Tim Disney is earnest and well-meaning yet isn’t bringing anything new to the dual conversations it endeavors to have.

William opens with anthropology professor Dr. Julian Reed (Waleed Zuaiter) giving a passionate lecture to his class about recently unearthed Neanderthal remains that possess enough genetic material to produce a clone. He argues that the study of a living Neanderthal could lead to numerous scientific breakthroughs ranging from physiological development to immune system studies, yet his repeated requests to proceed down this path have been rejected. After class, Reed is approached by Dr. Barbara Sullivan (Maria Dizzia), whose medical knowhow inspires him to forge ahead with his plans to actually bring a Neanderthal to life.

A whirlwind romance between the two doctors follows, as does a few damn-the-torpedoes conversations about the morality of Frankenstein-esque research. It all culminates in their unilateral decision to steal genetic information from the newly discovered Neanderthal’s remains to fertilize a clone egg that Sullivan will carry to term. Reed and Sullivan’s Neanderthal baby William is born, and the film spends most of its time from here jumping back and forth between scenes from William’s childhood, as well as a present-day narrative that tracks his transition between high school and college.

At every stage of William’s life, he has to overcome challenges ranging from the purely medical, to the obvious social, with the latter having far more impact on the boy than the former. William is freakishly strong, yet he’s no brute, as his cognitive abilities develop at the same rate as his human peers. And while he does seem to have some trouble grasping the nuances of humor and metaphor, he is more or less a regular, ordinary kid. With all of this positioned thus, Disney (who co-wrote the script as well) tries to peel back the layers of a very old debate about humanity’s responsibility to a world that is being made smaller by the advance of science.

The problem is that this is all well-trodden territory, and not just from the Neanderthal side of things. Sure, there’s Encino Man (which has a quick visual cameo in William) and Iceman, both of which examine the same narrative ground of introducing a “Caveman” to the modern world. But there’s also cultural touchstones like Frankenstein and even Jurassic Park, and they loom large, here. The characters in William speak and act like they’ve never heard of these stories or taken note of the lessons they imparted. When the hubris of humanity leads to the unnatural conception of creatures not meant for this world, conflict inevitably arises, and rather than examine this morality yarn from a different perspective, or perhaps challenge it in a new or interesting way, William just hits all the same notes of its predecessors.

Within this text, there’s also a sub-plot about the disintegration of Reed and Sullivan’s marriage along ideological lines. On the one side, there’s the wild-eyed Reed arguing for William’s pseudo-incarceration for study owing to the greater good, and on the other is Sullivan as the over-protective mother pushing for a normal, unexamined life. Once again, Disney’s intentions seem to be admirable, here, as this debate highlights a very real conflict in many parents’ lives: mainly, how much of a childhood should be spent prepping for adulthood rather than just enjoying the ride.

It just doesn’t scan, though. Reed and Sullivan are written as one-note narrative archetypes trapped in a story whose path and intentions are telegraphed with such obvious strokes that the “debate” never becomes one for the audience. Whether it is because we’ve seen Jurassic Park, or just because Reed is painted with such broad, villainous strokes, what’s coming for William and his development is obvious. The introduction of a tutor, Sarah (Susan Park), for adult William (Will Brittain), acts as an audience surrogate for viewers the film seems to think need an extra push to get at the themes written in bold letters across every frame of this thing. And while Park and Brittain do their best to sell this budding relationship, it all feels a little forced, and points towards conclusions that don’t need the extra direction.

Twin DPs Nelson and Graham Talbot shoot William with a lot of wide still shots highlighting William’s place in a larger world full of both possibility and danger. They make use of a number of shots of water and forests to highlight William’s place in a different era, when trees instead of buildings loomed large over the bipedal beasts roaming the land. Their visual deployment of windows as literal framing devices to highlight William’s place in the narrative as something to be observed is also a very clever and informative choice, and it elevates the material accordingly.

Taken as a whole, however, there’s just not a lot of new meat on the bone in William. The whole effort looks great, and moves along at a decent pace, yet it struggles to overcome its clunky dialogue and try-hard script to ascend to anything more than a basic retread of better, more ambitious fare.

Comments on this entry are closed.