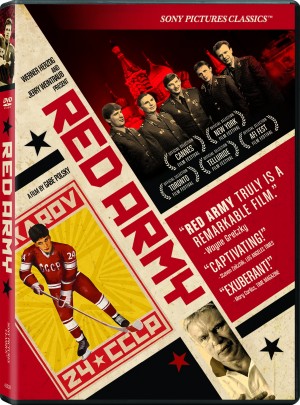

Red Army, a documentary out now on VOD, Blu-ray and available on DVD, was the nickname given to the Soviet Union’s Russian national hockey team. The lives of the Russian players featured in the documentary run parallel to the historical clashes between the Communist East and the Capitalist West. The Red Army’s captain, Slava Fetisov, is at the center of the film as he recounts his years playing for what was considered, until the fall of the Soviet Union, to be the world’s best hockey team.

The film’s most interesting aspect lies in its negative portrayal of the Soviet system and its simultaneous praise for the Communist ideals that the Red Army carried into each game. Fetisov’s equally bitter and nostalgic views of Russia are in conflict with each other, but the film concludes with praise for hockey as a kind of totalitarian sport infused with Marxist ideals.

Director Gabe Polsky, the son of Russian immigrants and a former hockey player for Yale University, focuses on Fetisov and allows him to recount the hard-won victories over a long career that eventually took him to the NHL in the United States. The dissolution of the Soviet Union allowed American hockey teams to buy up Russian players, who were considered some of the best players in the world. But the defection to the U.S. by some Russian players exposed the cultural xenophobia that was stoked by strong suspicions and outright hatred of Russians at the height of the Reagan years, and by the incomprehensible notion of individuality prevalent in American society, which confounded many of the Red Army members.

Footage of the Red Army practicing in their home country shows the strict regimentation and uniformity that they exhibited during their matches. Team work and conformity were emphasized and practically beaten into the Russian players, but few members of the Red Army express displeasure at having to give so much of themselves for the sake of representing their own country. The complicated plays and moves that the Red Army developed on the ice are described as an art form, and rightly so. Each player worked in perfect unison, in ballet-like precision. Matches are shown in which the Russian team glides effortlessly around their opponents towards the goal. But when some of the players joined the NHL, effectively defecting from their totalitarian country, they became disillusioned by the sport and by American ideals and patriotism.

Looking back on his time in the NHL with displeasure, Fetisov talks about what he described as the artlessness and lack of teamwork in American hockey while we’re shown NHL players fist-fighting on the ice and skating haphazardly without form or grace. The historical conflict between East and West during the Cold War years are woven into the Russians’ dismay at American hockey’s lack of conformity and discipline. One player who willingly left Russia to play for a U.S. team praises the U.S. economy for the opportunity to allow each man to be his own boss and keep all that he earns, but his facial expressions while proclaiming American freedom shows dismay at a foreign culture whose ideals are the opposite of those he grew up with. The film concludes with the dissolution of the Soviet Union coinciding with the loss of integrity and pride in teamwork that was instilled in Fetisov during all of those hard years of practice for his totalitarian homeland.

Fetisov has conflicting feelings about the hard clampdown by the Soviet Defense Minister who tried to prevent him from defecting to the U.S., and about the post-Soviet Russia that he returned to as the Minister of Sports under Vladimir Putin. He speaks with disgust about the open corruption of modern Russia, preferring the regimented systems of control that were in place during the Cold War years. Over footage of present-day Moscow showing diamond-studded cars and citizens using cell phones and wearing expensive clothes, the film makes the point that Western materialism and America’s romantic ideals about individuality and upward mobility helped to destroy the nationalism and pride of country that hockey propagated in Russia.

Throughout Red Army, Fetisov recounts the hardships of playing for a national team that subjected its players to grueling, prison camp-like practice regiments, and constant KGB surveillance. As the story of the team runs parallel to major events that occurred during the waning years of the Soviet Empire, such as the Soviet-Afghanistan War of the early 1980s, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev, the game itself loses its integrity just as the totalitarian country opens itself to the Western world. What was lost in this newly found openness to the rest of the world was, the film argues, hockey as an art form, as a sport that emphasized the collectivism and group identity that formed the basis of many of the Soviet Union’s ideals.

Red Army is remarkable for the way it explores the lives of people who had the misfortune of being caught living on the losing side of history. The Red Army may have been one of the best sports teams in the world, but they truly lost when Russia fell to the West. In a contemporary political climate stoked by unfounded fears of socialism, Red Army’s argument that hockey was emblematic of the positive aspects of Communism, which included teamwork and cooperation, is a provocative thesis. Shown from the losing side, Red Army shows the complicated nature of historical events.

Comments on this entry are closed.