In a Q&A at The Museum of Tolerance that appears on the Blu-ray of the harrowing Oscar-winning Holocaust drama Son of Saul, first-time writer/director László Nemes says that his challenge for the film was to translate an insider’s perspective into cinematic terms rather than subscribing to the usual post-war narrative of survival.

From that idea came the portrait of a man.

That man is Auschwitz extermination camp worker Saul Ausländer (played with solemn single-mindedness by Géza Röhrig), a Hungarian-Jewish prisoner. Son of Saul follows him quite literally, as Mátyás Erdély‘s 1:33 limited-scope camera is positioned mere feet or inches from Saul as he journeys through a real-life nightmare more harrowing and soul-killing than any horror movie could present.

Son of Saul is a one-of-a kind immersive experience that gives stark glimpses of death-camp murder and madness with a frightening frankness. Thanks to the cinematography of Erdély, who worked with Nemes on various first-person experiments for five years leading up to this feature, Son of Saul becomes more than a gruesome tour of the worst that humans are capable of. It becomes a portrait of an individual experience, told with unflinching honesty and spotlighting awful choices that we all hope never to have to make — on a minute-by-minute basis.

About film portrayals of The Holocaust: “If you use cinema to try to show and say a lot, then you end up reducing the fact,” says Nemes.

This statement encompasses what makes Son of Saul so powerful and unique. Cinematically, The Holocaust films we are used to seeing (and there have been plenty) are framed within modern storytelling conventions. Schindler’s List, for example, show plenty of the Hell on Earth, but it also takes the story of one man who finds courage by working through his own selfishness and uses it as a metaphor for the larger conflict.

Son of Saul has a tougher time finding easy places to moralize because the entire film the audience is stuck with the POV of someone whose morals have eroded to possibly subhuman levels. Subhuman levels which you begin to … actually … understand … and (is it possible) empathize with some of his decisions.

Gradually the merest of traditional plots reveals itself, and its as depressing as you might expect. Saul finds the body of a child that he thinks is his son. His goal, within the confines of the concentration camp, is to smuggle the body out and give his son a proper Jewish burial. This becomes Saul’s only focus, his own kind of moral survival — and because of Nemes’ pure presentation (one that doesn’t present the story in any easy genre categorization with character types that can be found in any other kind of movie), Son of Saul reaches a new kind of complex emotional height I’ve rarely experienced.

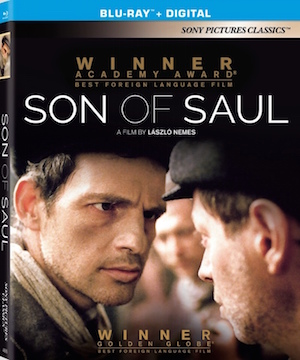

In offering a full slate of extras, including a deleted scene, the Q&A, and feature-length commentary with the film’s main creative trio of Nemes, Erdély,and Röhrig, this Sony Pictures Classics Blu-ray gives

“To kill God’s image in us is not enough to transform a person into a walking corpse,” says Röhrig. “Rather, to kill God’s image in us, the only way to do it is to undo our humanity.”

He’s talking about the Nazis dragging the Sonderkommando (the Jewish death camp workers who were forced to exterminate their own) down to their own twisted lack of morality, psychologically removing themselves from their own humanity. It’s interesting to hear the Q&A and listen to the commentary because my first viewing of Son of Saul was more visceral than intellectual. Listening to the filmmakers and watching and thinking about it again, it’s easier to understand that their instincts were entirely correct, and the film works exactly the way they planned.

.

Comments on this entry are closed.