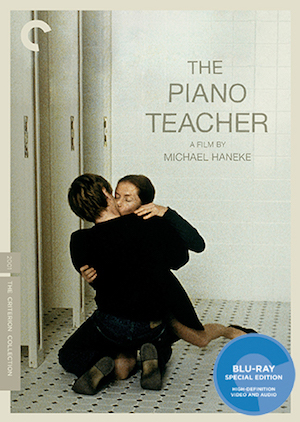

It’s clear from the opening scene of Michael Haneke‘s controversial 2001 classic The Piano Teacher, available in a new HD digital transfer on Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection, that some severely repressed feelings are lurking under the surface.

It opens with a vicious fight and subsequent make-up between 46-year-old Erika (Isabelle Huppert) and her mother (Annie Girardot), where the daughter pulls on her mother’s hair and strikes her. Then they go to sleep in the same bed. Her mother says: “No one must outdo you.” It will be a mantra for Erika that we will find out goes so painfully against every fiber of her sexual being.

In her life as a professor who demands something close to perfection from her students, Erika is indeed all about control. She’s an expert at controlling her own desires as well because, outside of her mother, the people in her life accept this one dimensional persona. By way of a warning, we learn off-handedly at one point that her father went insane in an asylum.

The Piano Teacher is shot in and around a Viennese conservatory, but this is not some hoity-toity drama of manners. No, Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek’s 1983 novel was provocative too, and her main character was even more expressive. Haneke is rigidly formalistic. He creates plenty of suspense and shock, even though there’s no actual score to assist him, just the diagetic music in individual scenes.

Huppert plays Erika like a woman detached. She cannot give up control. There are so many scenes where a massive change happens on her face even though she’s completely reserved. She’s a wonder.

When Erika meets handsome young adult Walter (Benoît Magimel), who desires to be her student, he mentions the “benefits of illness.” She talks of the composer Robert Schumann, who towards the end was losing his mind. Schumann knows it, Erika says, but he clings on one last time. She is focused on “the moment of knowing what it means to lose oneself before being completely abandoned,” and we know its foreshadowing, but it’s such a tease to so many possibilities.

Erika is seduced by Walter’s piano playing, but his confidence shows her that he is all about the seduction. It’s annoying. The way she feels already reveals that she’s likely to lose herself, as Huppert calls it in her commentary, “her impending destruction.” This domineering woman, who thrives in an institution built on hierarchy, is afraid of being used and abandoned. It’s the same woman who calmly and defiantly enters a private peep show room in an adult video store full of men. She’s afraid of losing herself in him. And sure enough — by the end of the film, she’s worse off.

Haneke shows a similar amount of restraint as Huppert, and it makes the truly dramatic scenes even more powerful. An infamous scene of self-mutilation is very hard to watch, but it’s also remarkable because it shows very little, and expresses so much. Another stunner is one seven-minute long take that is an emotional climax and a technical marvel, but isn’t showy at all.

New interviews with Haneke and Isabelle Huppert do a lot to illuminate the challenges of adapting a revered and troublesome work. Both director and actor were clear on their intentions from the start, and this alignment produced a movie that holds up as one of the best arthouse films of the last 20 years, with a nearly unmatched quiet kind of intensity. Also included on this essential Blu-ray is selected-scene commentary from 2001 featuring Huppert, and fascinating behind-the-scenes postproduction sync footage featuring Haneke and Huppert.

There’s a couple of authentic, candid working moments (during an ADR session) where the pair discuss the different meanings and syntax of one line, in both French and German. They try to sync up the timing of her line reading with the precise music and movement — an essential part of postproduction that is rarely seen. The dynamic is fascinating to watch and Haneke’s attention to detail is illustrated as Huppert is asked to re-do the noises her character makes in particularly violent scene. After absorbing the themes of The Piano Teacher, there’s also some kind of release, I suppose, in watching the filmmakers create that fiction, in the moment.

Comments on this entry are closed.