Two new DVD releases from Music Box Films explore unusual communities. One film shows the collective denial of a community shaken by accusations of abuse against one of its most prominent members, while the other romanticizes a group that chooses to live far from civilization.

[Rating: Solid Rock Fist Up]

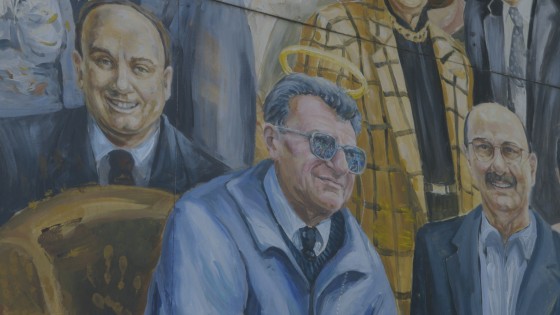

Amir Bar-Lev‘s Happy Valley deals with the reactions among college football fans of Penn State coach Joe Paterno’s culpability in Jerry Sandusky’s sex abuse scandal, in which Paterno was told by an assistant coach on the school’s football team that he witnessed sexual abuse of a young kid by Sandusky, after which Paterno and the school turned a blind eye to the abuse.

The Penn State community’s reaction to Paterno’s downfall allude to the ways that the cult of personality can blind devotees to the truth. As Paterno’s role in the scandal becomes apparent, the film demonstrates the Penn State community’s unwillingness to come to terms with the reprehensible actions of the figures they worship.

Early in the film, the state of utter denial of the pro-Paterno/Penn State community is best summed up by a Penn State employee who laments the loss of Penn State’s innocence when students riot after Paterno’s firing. Noticeably absent from the man’s observation, and from the students and other people involved in the Penn State football program, was sympathy for Sandusky’s victims. The film effectively conveys the mob mentality and mass state of denial that was a result of reverence for ideals that many believe college sports propagates, such as community and sportsmanship, which are twisted by some fans’ willingness to overlook Paterno’s role in the cover-up.

Happy Valley uses one student as a representative voice for the mass of supporters who rally mindlessly around a cult of personality that blinds them to the actions of Sandusky and Paterno. Penn State graduate Tyler Estright, a man in his early twenties, seems to take the accusations against Paterno as an affront to the values held by the Penn State community. Estright mentions Sandusky’s victims in passing late in the film while taking numerous opportunities to lament the firing of Paterno from Penn State and the coach’s treatment by the news media. Estright takes a clear stance regarding the victims when the former student comments over footage of a candlelight vigil for the abused children, “This seems so fake to me,” and, “I don’t care what happened, it’s about Penn State football.”

The film does a good job of using Estright to show how the devotion of many members of the Penn State community were unable to come to terms with the tarnished images of men that they’ve conflated, quite literally, to a God-like stature.

Happy Valley is refreshing in the clear stance it takes against its subjects. The film is somewhat reminiscent of the 2003 documentary Capturing the Friedmans, which also delves into a quiet community torn apart when one of its most upstanding citizens is indicted on child sexual abuse charges. Capturing the Friedmans was a frustrating film to watch because of the ambiguous stance it took regarding the guilt or innocence of the accused people.

That film spent much of its running time posing open-ended questions about the crimes that the Friedmans allegedly committed while portraying many of the accusers as outright liars and opportunists. Sandusky’s guilt and Paterno’s role in the cover-up of his crimes are foregone conclusions in Happy Valley. The subjects themselves openly display their own moral confusion and lack of concern for the victims, often in the name of preserving the revered institution of college football as a sort of American tradition, showing how cult-worship twists the values of a community.

[Rating: Minor Rock Fist Up]

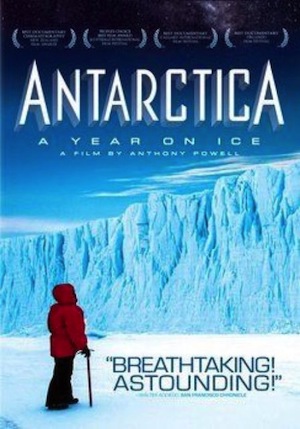

On a much lighter note, Antarctica: A Year On Ice also explores the notion of community through the lives of the scientists, vagabonds, curios adventure seekers, and other eccentrics who feel a pull from mainstream society towards lives as workers on the handful of isolated research bases on the Arctic landscape.

Anthony Powell, the film’s first-time director, proves to be a member of the eccentric community he films as he opens Antarctica by showing the viewers the time-lapse photography equipment he hand-built to capture many of the documentary’s stunning images. The film covers a full year in the lives of the scientists and others who keep the U.S.-led McMurdo Station and New Zealand’s Scott Base running through nightless summers and long winters in which the sun never appears. The group of people at the heart of Antarctica give the impression that mainstream society, with its modern conveniences, leave their need for adventure unfulfilled. Unlike Happy Valley, the people in Antarctica: A Year on Ice show the positive aspects of community, set against beautiful imagery, which is the real star of the film.

While many of the people in Antarctica are shown carrying out what would be, in any other place, everyday jobs (the film follows a store clerk, an office administrator, various technicians, and firemen), Powell’s film relies heavily on stunning visuals of the landscape to make his work interesting. Beautiful time-lapsed footage of aurora borealis and images of the sun hovering above the horizon for a full 24-hour period make up for somewhat uneventful portrayals of the people on screen. His surface-deep examination of the people in Antarctica is forgivable because of the arresting visuals he has created.

Powell creates little to no dramatic tension with the footage he shot. The female store clerk yearns for fresh fruit after spending months eating pre-packaged food, and we learn that Powell met his wife in Antarctica and married her six weeks later. We see the people from the various bases on the frozen continent bond during a Christmas gathering and during a film festival that Powell organizes. The uneventfulness of many of the film’s sections are broken up by hurricane-force snow storms and other images of the landscape’s natural beauty.

Antarctica: A Year on Ice can be recommended based on the quality of the images alone, but Powell misses opportunities to draw out the inherent weirdness of a group of people who choose to travel to the bottom of the planet to live on such a harsh landscape, but he makes little effort to understand why. He goes for a lighthearted approach, which may appeal to fans of Discovery Channel nature documentaries, or March of the Penguins, because Powell doesn’t view Antarctica as an alien place, hostile to human life, as Werner Herzog did in his 2007 documentary, Encounters at the End of the World. Powell’s film would still be watchable without the people he filmed, as his fascination with Antarctica is felt through his meticulous stop-motion footage.

Comments on this entry are closed.