This review appeared in slightly different form on the Scene-Stealers Lawrence.com blog, and a video review from KCTV5′s It’s Your Morning.

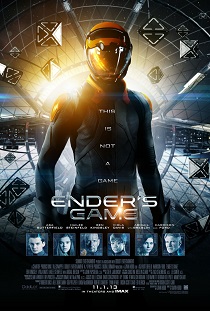

Summit Entertainment is the studio behind the recent young-adult mega-hit adaptations of the Twilight series of books and The Hunger Games, so it was with much trepidation and skepticism that I approached the company’s most recent stab at launching a kid-friendly sci-fi franchise, Ender’s Game.

Summit Entertainment is the studio behind the recent young-adult mega-hit adaptations of the Twilight series of books and The Hunger Games, so it was with much trepidation and skepticism that I approached the company’s most recent stab at launching a kid-friendly sci-fi franchise, Ender’s Game.

Based on the widely revered 1985 novel by Orson Scott Card—who lately has become more famous for his anti-gay rights remarks than his writing—the future-set Ender’s Game won as many fans for its detailed depiction of military strategy as it did for its thorny moral questions. Rights to the movie and proposed scripts changed hands so many times since the novel’s publication that it became known as an “unfilmable” book.

Perhaps it took 28 years for people to accept the idea of a 10-year-old commander with the power and authority to command lethal military might, but after the kill-or-be-killed reality show of The Hunger Games, it doesn’t seem like such a stretch for today’s youth culture to imagine. Ultimately, what makes writer/director Gavin Hood’s streamlined adaptation of Ender’s Game successful is its devotion to the awakening conscience of its main character, criticized by some as “the innocent killer.”

Asa Butterfield (Hugo) gives young Battle School recruit Ender Wiggin as tough an exterior as a 10-year-old can have when he’s being bullied for being younger and smarter than his teenage classmates. Everything about his training—the adult officers barking orders, the uniforms that don’t quite fit, the forced isolation, the videogames that read your mind and report back to the adults—is absurd. Harrison Ford plays Colonel Graff (an aptly named character considering the actor’s image), so desperate to fend off another alien attack on Earth that he’s willing to treat kids and their not-yet-formed, game-oriented brains like lab rats.

Asa Butterfield (Hugo) gives young Battle School recruit Ender Wiggin as tough an exterior as a 10-year-old can have when he’s being bullied for being younger and smarter than his teenage classmates. Everything about his training—the adult officers barking orders, the uniforms that don’t quite fit, the forced isolation, the videogames that read your mind and report back to the adults—is absurd. Harrison Ford plays Colonel Graff (an aptly named character considering the actor’s image), so desperate to fend off another alien attack on Earth that he’s willing to treat kids and their not-yet-formed, game-oriented brains like lab rats.

In one scene, Ender is being bullied by a teen. After he outsmarts his attacker, he kicks him repeatedly while he’s down and is thrown out of school. When asked why he kept hurting the boy, he replies that yes, he had won that fight, but he wanted to win all the subsequent ones as well. He is rewarded for his long-term strategy, however violent the solution, and this moment turns out to be the fulcrum of the entire film.

Hood balances Ender’s ascension in the military—filled with conventional but exciting montages about beating the odds—with scenes that, although all-too-obvious, challenge the morality of his situation. As a sympathetic major, Viola Davis has the unfair task of being the moral barometer pretty much every time she appears onscreen, but who better to fill that role than an actress who can make even the corniest dialogue feel natural?

Hood balances Ender’s ascension in the military—filled with conventional but exciting montages about beating the odds—with scenes that, although all-too-obvious, challenge the morality of his situation. As a sympathetic major, Viola Davis has the unfair task of being the moral barometer pretty much every time she appears onscreen, but who better to fill that role than an actress who can make even the corniest dialogue feel natural?

The plot moves efficiently forward, the special effects and set design are convincing, and the training-fight sequences are filmed clearly and with precision—even if they aren’t filled with the pages and pages of detail Card lent them in the book. In short, Ender’s Game plays surprisingly well. With its faceless insect-like enemy and militaristic bravado, it sometimes feels like Starship Troopers Lite, but then again the violent, darkly satiric approach taken in that subversive 1997 movie won’t be seen again in the likes of a big-studio franchise wannabe.

No, for a young-adult fantasy movie, Ender’s Game plays the material straight, and is surprisingly thought-provoking. When the movie asks its questions about leadership and questioning authority, it may seem like the strings are too visible, but that’s just to combat that natural youthful desire we have to win at whatever game we’re playing.

No, for a young-adult fantasy movie, Ender’s Game plays the material straight, and is surprisingly thought-provoking. When the movie asks its questions about leadership and questioning authority, it may seem like the strings are too visible, but that’s just to combat that natural youthful desire we have to win at whatever game we’re playing.

Because Ender is trained to fight his own tendency towards empathy from the beginning, it’s a feeling its audience has to grapple with throughout the film as well.

Comments on this entry are closed.