Here’s my TV review with clips of The Act of Killing on KCTV5′s It’s Your Morning.

A shorter version of this review appears at Lawrence.com.

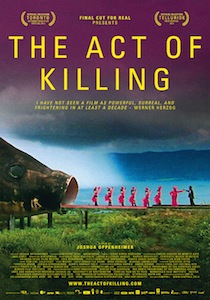

Opening at the Alamo Drafthouse in Kansas City this weekend is a remarkable achievement in the genre of documentary filmmaking called The Act of Killing that must be seen to be believed.

Opening at the Alamo Drafthouse in Kansas City this weekend is a remarkable achievement in the genre of documentary filmmaking called The Act of Killing that must be seen to be believed.

Legendary filmmakers Errol Morris (The Fog of War) and Werner Herzog (Grizzly Man) signed on as executive producers after seeing an early cut of this movie with the sole purpose of bringing more attention to it. Herzog himself said of the film, “I have not seen a film as powerful, surreal and frightening in at least a decade … it is unprecedented in the history of cinema.”

Director Joshua Oppenheimer uses a unique method to tell the story of Indonesian gangsters who carried out hundreds of thousands of death-squad killings following a failed coup of Indonesia in 1965 and the corruption that has reigned ever since. While also capturing standard interview-style and vérité footage of their paramilitary organization Pancasila Youth, he also asks the unrepentant and unpunished leaders (Anwar Congo and Herman Koto among them) to re-enact their versions of the killings for a film that they have complete control over. The fact that they are very willing participants speaks volumes of the way this dark time has been portrayed in their culture.

The result is a mind-boggling two hours, where the murderers are confronted with their crimes against humanity at every turn and in a variety of ways. There are no violent images of the victims. There is no perspective from the victims’ families. And that’s OK. Going down that path would lead to a very different film.

The result is a mind-boggling two hours, where the murderers are confronted with their crimes against humanity at every turn and in a variety of ways. There are no violent images of the victims. There is no perspective from the victims’ families. And that’s OK. Going down that path would lead to a very different film.

The Act of Killing is instead a fascinating exploration into the ways that guilt can manifest itself, especially when the offender has acted with complete impunity. These men are now celebrated as heroes in their culture. By slaughtering “the communists” and anyone else who got in their way or didn’t pay up, they have become the forefathers of their country. Remarkably, they somehow embrace the term “gangster” as having to do with some ultimate kind of freedom, and their government stands behind them. They’re essentially war criminals who were never tried, and their attitude is by turns boastful and blissfully unaware of the real cost of their actions.

The killers are eager then to make movies from their points of view. In this case, the styles of film they choose are a musical, a western, and a gangster film. Much more than this, however, is included in Oppenheimer’s documentary. The mall-like commercialism of modern-day Indonesia stands in high contrast to the stories told. A long history of governmental corruption isn’t just out on the open, it’s celebrated. Oppenheimer’s growing familiarity with his subjects allows him to broach heretofore off-limits topics and get brutally honest reactions.

The killers are eager then to make movies from their points of view. In this case, the styles of film they choose are a musical, a western, and a gangster film. Much more than this, however, is included in Oppenheimer’s documentary. The mall-like commercialism of modern-day Indonesia stands in high contrast to the stories told. A long history of governmental corruption isn’t just out on the open, it’s celebrated. Oppenheimer’s growing familiarity with his subjects allows him to broach heretofore off-limits topics and get brutally honest reactions.

The movie then turns in on itself for some of the most fascinating sequences. Congo watches clips of the film he’s making and brings his nephew in to watch him (in the movie) playing one of his victims, strangled to death by wire. It’s a scene we’ve already witnessed on the set during filming, so we know that Congo has a momentary breakdown and can only imagine what he’s thinking as he portrays one of his own victims. Looking at it later, however, all he can think about is how proud he is that his nephew can see Grandpa in a movie.

Structurally The Act of Killing is a challenge, as it contains no single narrator or fixed perspective. As the film progresses, it bounces even more frequently between this culture of justification and denial and the increasingly absurd re-enactments. Watching Congo and the others who have committed these atrocities finally wrestle with their moral conflict — each in unique ways, if at all — leaves a devastating impression of the banality of evil.

Read Scene-Stealers contributor Abby Olcese‘s take on The Act of Killing and listen to Trey Hock’s interview with The Act of Killing director Joshua Oppenheimer.

Comments on this entry are closed.