While trusted advisors such as Skot K., K. Render, and Mean Melin are often an inspiration during a list’s inception process, I have to give myself full credit for cooking this one up. Sitting at my second home, Sun Liquor, having a bourbon, I thought that I was pretty thirsty when I took my first delicious drink of whiskey, only to realize that I wasn’t actually thirsty, just alcohol hungry. This got me thinking about what really constitutes “thirsty,” and what it means to be truly in need of a drink (alcoholic or otherwise). Immediately, the bent, rusty wheels of my mind began turning as ideas sprang out of the whiskey ether to form a tentative ranking of the thirstiest moments in film. Besides, it’s been awfully fucking hot in the U.S. as of late, so it seems altogether appropriate that a list detailing the driest, most parched moments in cinema history be offered up this day.

While trusted advisors such as Skot K., K. Render, and Mean Melin are often an inspiration during a list’s inception process, I have to give myself full credit for cooking this one up. Sitting at my second home, Sun Liquor, having a bourbon, I thought that I was pretty thirsty when I took my first delicious drink of whiskey, only to realize that I wasn’t actually thirsty, just alcohol hungry. This got me thinking about what really constitutes “thirsty,” and what it means to be truly in need of a drink (alcoholic or otherwise). Immediately, the bent, rusty wheels of my mind began turning as ideas sprang out of the whiskey ether to form a tentative ranking of the thirstiest moments in film. Besides, it’s been awfully fucking hot in the U.S. as of late, so it seems altogether appropriate that a list detailing the driest, most parched moments in cinema history be offered up this day.

I didn’t want to exclude people who were anything less than on the brink of complete desperation and/or dehydration, for a few examples below (notably #6) showcased a scene where a person just really, really needed a drink, and weren’t exactly in danger of dying without one. To get higher consideration for a ranking, however, the more dangerous and pressing the thirst, the better, thus the cruelest moments of water-longing got higher priority. One especially close call included Tremors, which damn near made the cut since somebody in that film did indeed die of thirst while trying to wait out the graboids (Ol’ Edgar), yet since we never met that character or witnessed the demise, I had to pass it over. Some other near-misses included Spaceballs, The Flight of the Phoenix, Victor Victoria, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Babel, Ishtar, and Dick Tracy (which I didn’t have the heart to so much as write about, let alone praise in any way). Though not every film listed had a clear-cut case of dehydration, all of them involved a person or persons who were in desperate need of a drink to keep going for any length of time. Finally, it should be noted that in an earlier incarnation of this list, Open Water slid in at the #10 slot, only to be replaced in today’s 2.0 reboot by a more recent film, one where thirst and dehydration played a very important role…

Fans of the 10rant probably recognize this one from the Top 10 Self-Surgery Scenes in Film list, and also from the Top 10 Bone Breaking Moments in Film list, where Aron Ralston’s self-surgery earned him the #1 and #2 slots, respectively. For those unfamiliar with Danny Boyle’s gripping, character driven film, 127 Hours, it told the true story of outdoorsman Aron Ralston, who in 2003 went hiking alone, and stumbled into a crevasse in such a way as to become trapped. In falling, Aron (James Franco) had dislodged a boulder, one that pinned his arm against the canyon in a manner that left him trapped, standing in place, with only 20 or so ounces of water at his disposal. What was worse, he was in a secluded part of the park with absolutely no one informed as to his whereabouts or plans for a return. Thus, what had begun as a defiant expression of independence and self-reliance had quickly turned into a death trap, for all the steps the hiker had taken to assure that he was truly alone, and on his own, now assured that he was indeed all by himself, and in a fabulously shitty position.

Days went by as Aron explored all the ways he might set himself free, for even with the use of just one arm, the outdoorsman proved himself to be a very sharp, resourceful guy. Using his climbing ropes, Aron attempted to rig a pulley system to hoist the rock off his arm, and even used a pocket utility knife to try and chip away at the canyon wall and offending boulder: all to no effect. All of this work kept Aron busy, and as a result, pretty damn thirsty, something that director Danny Boyle didn’t neglect to play up as the audience’s desperation and anxiety climbed right alongside Aron’s. Though the penultimate “squirm” scenes were undoubtedly the arm-removal parts (yes, it went on long enough to qualify as more than a single scene), earlier moments where Aron labored to free himself amidst thoughts of forgotten Gatorade bottles and ice cold sodas were just as effective. And while he didn’t complain nearly as much as this next trapped fellow, one maybe even more thirsty and in even worse surroundings, Aron definitely suffered his fair share…

I almost forgot about this one, and had I done so, I would have felt pretty ashamed. I watched the hell out of this movie as a kid, and think of it today as Lord of the Rings: Lite, for many of the same things that drove the latter film and its success were at play in Willow. After all, one need only look at the plot and themes of Ron Howard’s wanna-be epic to see the glaring similarities. It was about a little person from an unassuming village who travelled through dangerous, fantasy-laden territory with a precious token that promised to rid the land of evil if brought safely to its chosen destination. Along the way, the tiny adventurer happened upon an unrivaled swordsman and warrior who helped him on his journey, and would ultimately lead the good forces of the land to victory while the half-sized adventurer took care of the special mission. Whether it was a baby or a ring, the central elements of each story drove the larger narrative which had themes reminiscent of Tolkien’s original masterpiece in varying degrees.

And that’s okay. When I saw this movie as a kid, I didn’t know thing-one about Bilbo, Frodo, Aragorn, or Gandalf. Shit, about the only thing I read outside of school was the dialogue text that popped up during Nintendo gaming sessions. Thus, what I saw on T.V. was God’s honest truth, and I took it all as original and from the unique corners of whatever year I happened to be slogging through. At the beginning of Willow’s second act, when the diminutive hero came across Val Kilmer’s “Madmartigan” in a death cage, things were moving along briskly. Imprisoned for a crime and left to die a slow, thirsty death, the trapped swordsman was at first violent about his desire for water, then switched gears into sympathetic pleading. The whining and begging was relentless, and for a good ten minutes of the film, Kilmer hounded Willow and his companion for just one measly sip to drink. My favorite part of the vignette came when Willow was on the brink of giving Kilmer’s character some water, but got distracted and let the cup fall: streams of H20 passing through the poor bastard’s hands as he got just a few drops of relief. A fun movie, if not an especially good one (at least in hindsight), it did have a pretty thirsty moment, one that earned it a humble #9 spot.

Oh, Cast Away: others may not like or appreciate you, but I do. Maybe it’s because I experience periodic moments of melancholy, and will sometimes seclude myself so as to shield my friends from the depressed wrath of a sullen man, or worse, do so hoping that the isolation serves to insulate me from the dark thoughts that encroach upon a mind looking for misery scapegoats. Still, when feeling blue, this movie tends to cheer me up. It probably has something to do with the feeling a person gets when in self-imposed exile, knowing that if nothing else, one can at least rely upon themselves, a theme this movie explored to an exceptional degree. Tom Hanks’ “Chuck Noland” went straight-up Robinson Crusoe after his FedEx plane crashed into the Pacific Ocean, and he washed up on a deserted island. Left to his own devices, Chuck showed a remarkable amount of resilience, along with some stunning ingenuity and foresight, as he used pretty much every resource at his disposal effectively. Almost as a cruel joke, a pair of ice skates washed ashore, something many people might have discarded in wild frustration, but which Chuck used masterfully in any number of situations that demanded a make-shift tool.

Chuck used dress material from a prom gown as a fishing net, video tapes as woven rope, and a volleyball as an essential, sanity-maintaining silent companion. Yet near the beginning of his ordeal, the most pressing concern was a lack of water, as the island seemed to have few resources to provide a fresh drinking source. In one of the best scenes of the film, Chuck tried desperately to get at the fluid inside a coconut: his thirst at a desperate level. The man tried any number of different strategies to get the damn thing cracked open, my favorite attempt being his hurling of the coconut against a rock embankment. Yet when he finally succeeded and got the miserly thing opened, the impact of the blow busted the prize apart and left Chuck with but a few scant drops of fluid. The desperation in his eyes said everything about the scene, and with a little patience and ingenuity, he was able to develop a system whereby a smaller chiseling device opened a careful incision to get the juice out efficiently. The desperation leading up to this victory was heartbreaking however, and there are few actors out there who could have done a better job conveying that to the audience than Mr. Hanks. Well done, sir, you once again showed why you have two Best Actor Oscars while many have not even one.

Though people have sort of turned on this movie in the last twenty years, I’m still willing to go to bat for it, and to vouch for its quality. While it may be true that Chevy Chase is an unredeemable pig’s vagina, there was a time when the guy was pretty funny, something this film captured in the man’s waning years as a legitimate comedy threat. To counter-act the assholery, the picture presented Steve Martin and Martin Short, two fellas as nice and respected within the industry as Chevy is despised. 3 Amigos was a sometimes parody, sometimes homage to Seven Samurai/The Magnificent Seven, and succeeded mainly because it never took itself all that seriously. Though it told the story of a trio of haughty actors in the early twentieth century, it could have just as easily been set in any decade, for the actions and habits of Short, Martin, and Chase’s characters spoke to a broader, well-established theme in Hollywood: mainly that actors are spoiled pansies.

After getting kicked to the curb when they callously demanded a raise, the three unemployed actors got a telegram from a desperate woman named “Carmen” (Patrice Martinez) in an oppressed Mexican village asking for the assistance she believed only the 3 Amigos could provide. Yet since movies were still a new medium in 1916, Carmen didn’t quite grasp that she was hiring actors, and not actual killers. A comedy of errors ensued whereby the three actors were disgraced, then sought redemption by assuming the actual mantle of real heroes. In one of the film’s funniest moments, as the 3 Amigos were riding through a brutal desert, panting like whipped dogs for lack of water, one Amigo reached for a canteen only to find a solitary drop or two inside. The second followed suit and got a mouthful of sand. The third, Dusty Bottoms (Chevy Chase) went ahead and lathered his face and mouth with a full canteen’s worth of water, only to throw the generous remainder thoughtlessly to the ground, allowing for the precious water to seep into the thirsty, arid sand while his companions looked on miserably. A totally dick move (and hilarious), it’s pretty fitting that it came from Chevy. Speaking of westerns, though, we should spend a little time talking about another 80s classic that doesn’t get a lot of credit these days…

This movie had two thirsty scenes, the first near the beginning, when Scott Glenn’s character happened across Kevin Kline, who had been mugged in the desert and left for dead by his attackers. On the verge of death for want of water, Glenn’s “Emmett” gave the dying “Paden” a drink, saved his life, and instantly formed a tight bond with the smooth-talking gunslinger. The two men decided to ride together for a bit, and came across Emmett’s brother (Kevin Costner’s “Jake”), and a traveling Danny Glover (“Mal”), the former locked up and scheduled for a hanging, the latter refused service at a saloon just because he happened to be black. Emmett and Paden watched as Mal explained to the bartender that he hadn’t had a drink of whiskey or the comfort of an actual bed in quite some time, and that he was willing to pay handsomely for both. Being a racist buffoon, the bartender refused both, and threatened to rough Mal up with the help of some patrons if the thirsty cowboy/butcher didn’t make for the exit.

Proving that he was indeed thirsty, and willing to tussle for his long-desired whiskey (something this author can readily identify with), Mal absolutely manhandled the crew that tried to teach the parched man a lesson. Handily defeating all his attackers, and told that he had to clear out of the town’s jurisdiction, Mal took a moment to have his shot, and relished the beverage he had fought so hard to earn. In deciding whether to rank this scene, I struggled a bit, for Mal wasn’t in danger of dying without that shot. However, since this film also presented a genuine moment of dehydration with Kline’s character in an earlier scene, I decided to give this picture an honorable slot, for two thirsty vignettes in one film deserved recognition on such a list as presented here today. Besides, it was a good lesson to all, for it’s a bad idea to get between a thirsty man and his whiskey. But since we’re on a western kick here, let’s turn our attention to the new standard for that genre, and what many consider (this author included) to be the finest western ever made…

Of all the films on the list today, this one is my favorite. This is a respectable statement, for there are a number of movies presented today that are among my all-time favorites, so for this one to stand above the rest is quite an achievement, and is due in no small part to exquisite performances and nearly unrivaled filmmaking. I’m going to bypass a plot summation in the assumption that you have seen this movie, for every person should. Clint Eastwood’s “William Munny” was plagued with an inability to cope with death in this picture, for he was both unable to reconcile the horrible acts of his past, but also the trauma that came with the loss of his wife. Let me preface this section of the write-up to give credit to Dr. Herbert M. Stein (at least I think that’s who wrote the article), who wrote a psychoanalytical review of Unforgiven (which you can read in full here. The article outlined how Munny never came to grips with his past and his complicity in the death of so many people. Haunted by the very thing he delivered callously to so many people (death), Eastwood’s character was only able to mollify his conscience by becoming that thing which he most feared: the Angel of Death. Dr. Stein outlined the psychoanalytic concept of “identification with the aggressor,” which is a condition whereby a person assumes the role or actions of what they fear most so as to overcome that internal hindrance. Though the Schofield Kid character initially admired Munny, and asked for details of his previous exploits, Munny shied away from this admiration and seemed to fear the universal retribution that would ultimately find him, and pay him the same compliment in return.

By reminding him of his past, and asking Munny these questions about death, the Kid was breaking through the defensive barriers that Eastwood’s character had put up to shield him from such haunting thoughts. The most striking moment of the film came when Eastwood, the Kid, and their partner Ned (Morgan Freeman) fell upon the more sympathetic of their two marks, and shot the somewhat helpless “Davey.” Though Munny had showed a higher degree of empathy toward others during the film, his psychological make-up had obviously released any need for rationalization or justification for his acts, and once he’d shifted back into a killer, into his association with that which haunted him (death), Munny showed his true colors. As the gut-shot cowboy cried out for water, Munny demonstrated that he was still an empathetic presence, if not a forgiving one, and told the man’s friends that they could tend to “Davey” without fear of being shot. The moment came about masterfully, for Eastwood played the scene for the effect that was obviously the intended mark: that in the “Old West,” people died, and those that did the killing didn’t always have a reason, nor was there much sense to be drawn from the act(s). Though Munny killed the man, and felt bad about it, this didn’t mean that he had any redemptive qualities, or that the audience was any wiser, or comfortable after the fact. As in real life, like in the real “Old West,” people died for all kinds of reasons, most of them shitty. As in life, things often occur outside the bounds of reason, and as Munney so poignantly put it at the end of the picture, when responding to a dying man who claimed that he didn’t deserve to die, “deserves got nothing to do with it.”

Another one of my all-time favorite films, this one also has the distinction of being a biopic about one of my personal heroes, T.E. Lawrence. When looking back on your life, however long it has lasted up to this point, you’re likely to feel ashamed when measuring it against the exploits of what this guy did in a span of less than fifty years. This dude essentially taught himself how to read, then as a teenager took the initiative to learn one of the most difficult languages any westerner can tackle: Arabic. This he did just for the hell of it, and also became fluent in Turkish, French, German, Greek, and Latin. To broaden his horizons at the age of nineteen, he took a three month, one thousand mile walk through Syria, then came back and graduated college at the top of his class due to an inspired thesis that utilized the knowledge gained from his travels. When World War I broke out, he enlisted in the Army, and as a result of his archaeological work in the Middle East as a post graduate, was a rare commodity for the allies. Between the ages of 20-23, the guy had done extensive mapping of the region for the British government, and had updated centuries old maps to accurately assess water sources and travel routes for any army passing through the region (specifically the Negev Desert).

Britain’s Arab Bureau cooked up a scheme to use the various Bedouin tribes in modern day Syria, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia to harass the Ottoman regime in that region, and to tie those forces down via a series of guerrilla raids along vital supply routes. In Lawrence of Arabia, the film detailed this portion of Lawrence’s life, and gave a cinematic treatment of the British revolutionary who took it upon himself to help an undefined nation earn its independence and freedom. Assigned to lend whatever technical assistance and advice he thought beneficial, Lawrence organized, trained, and spearheaded campaigns that made the Turks howl. Perhaps his most impressive feat was the proposal of an overland campaign to take the strategically vital port city of Aqaba. To get to the fort, Lawrence and his small band of soldiers had to cross a blistering expanse of desert nicknamed “the sun’s anvil.” Though they passed through it successfully, once on the other side, they learned that one of their crew had stumbled and had been left behind without his camel. With no water or any hope that he might get to the other side, the soldier’s death was assured, or at least it was if no man had balls sizable enough to go back into the inferno to save him. Luckily, Lawrence had stones big enough for any two men, and battled the heat to save his boy. The scene where the stranded Gasim was stumbling through the hottest part of the day, mouth open, on the brink of death, was absolutely savage. Later on in the film, after Lawrence and his aide crossed Mt. Sinai and arrived at the Officer’s Club for a lemonade, the audience got another look at some serious thirst. Though the film played fast and loose with some of the historical facts, it did accurately capture the spirit of T.E. Lawrence, a guy who made a habit of accomplishing the impossible and defying all expectations, thirst be damned.

This film was pretty damn great, and was a stunning example of a hyper-realistic picture that defied the odds in a time when a majority of released movies were as genuine and believable as your average cartoon. It told the story of a rich, haughty, yet resilient prick (Robert Ryan’s “Carson”) who went out into the desert with his cheating whore wife (Rhonda Fleming’s “Geraldine”) and conniving business partner (William Lundigan’s “Joseph”). Carson broke his leg near the beginning of the film, and rather than go for help, his cunt spouse, who had already been slamming the partner, Joseph, left the poor bastard to die so that she could inherit the estate and elope with homeboy’s “friend.” That bitch. Believe me, she came an eyelash away from making the Top 10 Movie Bitch list, but since her aim was murder, the conditions of that ranking excluded her from contention.

Thing of it was, Carson was no push-over, and though he had spent the better part of two decades smothered in excess and a delicious alcohol addiction, the thought of taking his sweet, sweet revenge and surviving the ordeal lent the tycoon focus, and he pulled his shit together to make it out of the blistering hell-hole alive. And hell-hole it was, for the man had to brave all manner of desert creatures, not to mention the unforgiving sun, to make it out in one piece. Not only did Carson have to battle the heat and his growing thirst, he had a broken leg to deal with, not to mention the blinding rage that overtook him at pretty much every turn. As a funny aside, this was one of the last 3-D films that really got a studio push during the 1950s, when Hollywood was cranking these fuckers out en mass (sound familiar??). As will almost certainly be the case with the current fad, that 3-D explosion of the mid-20th century eventually died out, for people realized after a while that what they really wanted wasn’t slick special effects and campy glasses, but rather a damn good story. Luckily for them, this movie brought both to the table, and the result was a gripping yarn about a man rising above his own limitations and the expectations of his peers to come out on top: cold revenge dish at the ready. Damn straight.

An oft overlooked Alfred Hitchcock classic, this film originally got some bad press when released because of the even-handed treatment of German characters in the picture. To be fair, when this movie came out in 1944, the Nazis were tearing ass all over Europe and murdering the fuck out of people. Always the thoughtful filmmaker, however, Hitchcock was able to see through the propaganda of the period and to present a story that both recognized the genuinely evil nature of the Nazi regime, but also allowed for a more complex understanding of one’s “enemy” during wartime. The film centered around a group of people stranded on a life-raft after their ship had gone down, and dealt with the moral dilemma of ends justifying means, not to mention the imperatives of survival versus humanity in a desperate situation. Aboard the lifeboat were Americans, Brits, a German-American, and a German sailor who had been aboard the U-Boat that had sunk the survivors’ ship. The members of the lifeboat had to contend with the merits of each survivor, and who “deserved” to live based on class, nationality, and gender, for the supplies on hand were limited.

The complexities of the moral dilemma were never glossed over, nor were they sugar-coated, something which is a credit to the script’s author, John Steinbeck. It helped that the film’s author was one of the greatest literary minds in American history, and that his superb narrative was put in the hands of one of the most skilled filmmakers the world has ever known. Though the survivors were cooperative and optimistic at the onset of their dilemma, as exposure and dehydration gnawed away at their collective resolves, paranoia and fear evolved into outright murder and savagery. For a country at war, the film presented some challenging questions about who deserved life, and who has the power to grant such a prize. Though the obvious choice would have been to toss the German sailor overboard or perhaps even the German-American by way of association, the film never catered to this tendency as did other films of this period, pictures that were not embarrassed to out-hate other movies in their presentation of Japanese and German people. A fascinating character study, Lifeboat was also a desperately thirsty one, and created a very tangible sentiment of suffering both through the actors’ performances, and Hitchcock’s skill at constructing the scenario.

1. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966)

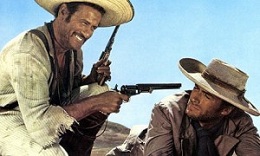

A classic in every sense of the word, this film set a standard not only for professional “Hollywood” filmmaking (ironic since it was shot outside the U.S.), but for the craft of storytelling as a whole. To a person, pretty much everybody with a speaking role in this film was a cruel, hard-hearted bastard with varying levels of evil buttressing their character. From the cold and calculating with little to no hope of redemption (Lee Van Cleef’s “Angel Eyes/Bad”) to the deplorable yet sympathetic (Eli Wallach’s “Tuco/Ugly”), down to the evil though identifiable (Clint Eastwood’s “Blondie/Good”): all the main characters were bad guys. With the exception of “Father Pablo,” Tuco’s long-lost older brother, and perhaps the sympathetic Union Captain at the Battle of Branstone Bridge, there wasn’t a character in this film that could be called anything but “bad” in the traditional dichotomy of cinematic ideology. After all, the most identifiable character, Blondie, left his partner (albeit a whiny, complaining jack-ass) to die slowly and with no small amount of misery via a long stretch in the desert!

It was this vignette, and the scene when Tuco returned to civilization for water and a gun, that inspired this list, for when it comes to thirsty scenes in film, this one shoots right to the top. The blisters on Blondie’s face, and the agony he had to endure at the hands of a delighted, water-chugging Tuco were absolutely brutal, and makes a fella appreciate a ready supply of water in civilized society. Indeed, as Blondie staggered toward the abandoned stagecoach near the end of the ordeal, his lips cracked and bleeding from exposure, the audience truly knew the man’s thirst. Director Sergio Leone’s re-imagining of the western genre via a return to a more simplified, violent setting injected the film and the movie industry with a brash inhumanity that revolutionized cinema and the craft as a whole. Kick-ass thirst scene aside, this movie was absolutely tits.

{ 2 comments }

Warren,

This list is brilliant. I laughed about each one as I scrolled through. Well done.

Now I’m off to get a drink.

Thanks, Trey! Hope the drink was as kind on ya as the list was!

Comments on this entry are closed.